PHOTO: Michael Edwards / Alamy Stock Photo

Paraguay is a small, landlocked country in South America. You’re probably not able to identify it on the map, but it has the second-largest forest in Latin America, behind only the Amazon rainforest. The region also has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. The country is now on fire because of that, and the fires are exacerbated by an unprecedented drought and heatwave. Here’s what you need to know and how you can help.

“Our country is on fire”

Here are the words from one Paraguayan: “Paraguay has often been the butt of jokes in Hollywood. A forgotten little piece of land in the heart of South America, we are but 7 million people. A rich, beautiful land of red dirt, lapachos and capybaras. You may have never heard of it, but today we are asking you to google us. Because our country is on fire. Several cities such as Areguá, San Bernardino, even our Capital, Asunción, have been burning for weeks now.”

“We are losing every single bit of green in our cities. As we write, the national Zoo and Botanic Park is on fire. Grasslands near our only international airport are on fire. The smoke can be seen through satellites. There is not a single city that isn’t plagued by these fires or the remnants of them. But all of that is just the tip of the iceberg. Our real problem is that no one is doing anything about it. Firefighters are begging for water, supplies, even food. You need to understand, our Firefighting Forces are voluntary. There is no funding from the government. There has not even been a formal acknowledgement about these fires. It is the people, us, who are trying to organize and help. This is why we are writing. We are begging you to help.”

But why is Paraguay on fire?

WHAT'S HAPPENING IN PARAGUAY🇵🇾

Something that no one is talking about (thread in english for my international mutuals and non-mutuals):#ParaguaySeQuema #ParaguayOnFire pic.twitter.com/DZk1zeyHtk— Ambar*🏴☠️ (@Arod_a_) October 2, 2020

Climate change, deforestation and state inaction: a deadly mix

Guillermo Achucarro, a climate policy researcher at Base-IS research centre in Asunción, says to the Guardian that weather conditions were making the wildfires worse. Paraguay is experiencing one of its worst droughts of recent decades, while simultaneously going through a record heatwave. Its Congress has declared a state of national emergency to transfer more resources to its—voluntary—fire service, but its citizens are disappointed with the lack of urgent action. “The same thing happens every year, and every year it’s as if it were a surprise,” says Achucarro. He notes that 2019 saw fires devastate approximately 325,000 hectares in the Chaco, an ecologically significant region in Paraguay (more on that later).

In fact, Paraguay’s Vice-President, Hugo Velázquez, claimed that fires were mainly started by citizens burning their domestic waste. While that is in fact happening, Achucarro emphasises that these fires are directly linked to the ongoing high rates of deforestation. Cristina Gorelewski, head of the National Forestry Institute, concurs, saying that most of these fires are linked to burning to clear land for cattle ranching, land invasions and illegal marijuana cultivation.

The blanket statement, however, that deforestation is to blame obscures the finer details and doesn’t tell us anything about who is responsible for this deforestation. But before we get into the complexities of the drivers behind deforestation: a word on Gran Chaco.

Gran Chaco: one of the most deforested areas on Earth

You’ve heard of the Amazon rainforest, but probably not Gran Chaco, South America’s second-largest forest. Verónica Quiroga, a biologist, says that it’s “a dry forest, and the lack of water takes away its colo[u]rfulness. That’s why, for the public, it isn’t very flashy and it goes unnoticed.” But it is home to great biological diversity, housing a wide variety of ecosystems and three major types of forest. It spreads across four countries: Argentina (60%), Paraguay (23%), Bolivia (13%) and Brazil (4%).

And what does “Chaco” mean? “Chaco”, according to the Royal Spanish Academy, is derived from the Quecha (an ancient, Indigenous language) word, “chacu”. “Chachu” is a type of hunting historically done by Indigenous communities in South America. Hunters circle around the targeted animal, before closing in to kill it. But before anyone tries to point fingers at the Indigenous peoples for “contributing to ecological destruction”, let’s keep in mind that it’s been proven that nature is better protected by Indigenous communities than the rest of the world.

We’ll circle back to how Indigenous communities are related to this issue later, but for now: let’s talk deforestation.

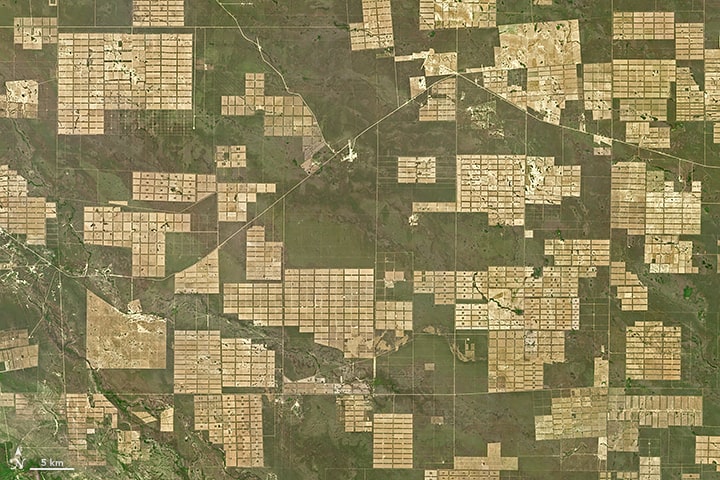

Unlike the “fishbone” pattern of deforestation in the Amazon, deforestation in the Gran Chaco tends to leave large rectangular clearings that reflect careful surveying by large-scale cattle-ranching operations. (NASA Earth Observatory image by Michael Taylor)

Cattle ranching and soybean cultivation: the expansion of the agricultural frontier

According to Guyra Paraguay, more than 2.9 million hectares of Chaco forest was deforested between 2010 and 2018. In June 2018 alone, an area of forest nearly twice the size of Buenos Aires was wiped out. 80% of the deforestation took place in Argentina. Matías Mastrángelo, a conservation biologist and an expert on the Gran Chaco, explains that this was because of events that occurred between the late 1990s and 2010. “The boom began with the arrival of genetically modified soybeans to Argentina. This caused agriculture in the Pampas region to displace livestock, which was, in turn, pushed over to more marginal spaces, mainly in the semi-arid Chaco.” Soy cultivation became a “driving force behind the deforestation of large areas of the humid Chaco in Paraguay and Argentina.”

Cattle ranching is another driving force: “cattle pasture [is] displacing forest at a rapid pace – even in areas that are officially protected.” Why? Paraguay is one of the top ten meat exporters in the world. And most of this meat comes from… the Chaco. The industry netted profits in the billions, which explains why the government relaxed environmental regulations in 2017. (In a 2017 decree, Paraguay’s ex-President Horacio Cartes authorised farm owners and livestock farmers in the Chaco to clear 100% of their land.)

Today, wealthy businessmen are allowed to operate basically without an environmental license. So much so that it’s impossible to tell what activities are legal or not. The judicial system is also lacking, and impunity for ecological destruction remains rampant. A recent report highlights that effective monitoring systems are not in place, and that “a significant amount of work [needs to be done] to get to the goalpost of zero-deforestation.”

Dirty supply chains: a nexus of government and corporate power

All this gets at the answer to the larger question here: who is responsible for the ongoing deforestation devastating Gran Chaco? With Paraguay ranking as one of the top beef-exporting countries on Earth, and noting that it’s exported nearly nine million pounds of leather in 2018 to EU companies including BMW, Porsche, Ferrari, etc., it’s easy to conclude that we—global consumers—should just boycott South American animal products. (After all, studies have shown that no commodity in the world is responsible for more deforestation than Paraguayan beef and leather.) But while that’s certainly part of the solution, it’s also the easy way out.

It’s the nexus of government and corporate power that we have to deal with too. On one hand, we have big corporations who aren’t held to account. There are 81 companies in Paraguay known to produce and/or procure cattle products like beef, dairy, or leather. But only 15 have committed to addressing deforestation in their supply chains. Most don’t even mention sourcing from Paraguay. On the other hand, we have a deeply corrupt government. 90% of Paraguayan land is “held by a few thousand rich agribusinessmen, from whose ranks its leading politicians are drawn.”

It’s clear now who wins, but who loses?

Stolen land: Indigenous communities fighting back

2% of Paraguay’s population identifies as Indigenous, and many of them depend on the forest for their livelihoods. The vast majority of their traditional lands have been stolen by agribusiness. They are the ones who stand to lose in this situation. Yet, as Joel E. Correia, an assistant professor of Latin American studies and core faculty member in the University of Florida’s Tropical Conservation and Development Program, highlights, “recent reports from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Open Society Justice Initiative show an alarming trend: Indigenous peoples often do not have a place at the table to influence the policy decisions and development initiatives that affect their communities.”

“Paraguay has no law or clear policy framework to facilitate protocols of free, prior and informed consent, as required by the International Labor Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, which Paraguay ratified in 1993. Moreover, the government agency that is charged with adjudicating indigenous affairs is one of the least-funded federal entities in the country. While there is a national legal framework to support indigenous rights, in practice, indigenous communities are often disproportionately affected by deforestation due to a lack of access to secure land tenure and a general lack of institutional support for their well-being.”

The Indigenous communities are still fighting (see: an ongoing case concerning the Ayoreo Totobiegosode people, who are being threatened by the expansion of cattle ranching). But they will not win this fight alone.

What can we do?

The most immediate action that you can take is to donate to the voluntary firefighting force. This, of course, will help in the short-term. You can also signal-boost this issue since it’s not been covered by the traditional media—certainly not as much as when the Amazon fires happened last year.

(But on that note, the Amazon is also on fire this year, and it’s worse than the last. The situation is so bad it’s nearing its tipping point. And by the way, that has to do with big agribusiness too. Check this out to find out more about the companies behind the burning of the Amazon, and read this investigative report to find out more about the situation on the ground. Here’s a report that came out in December last year about Amazon beef farming zones, and read more here about how consumer demand in one country can lead to another paying the price.)

In the long-term, as an individual consumer, you can consider finding out where your animal products come from. Or try to cut animal products out of your diet and life completely. But, as always, we need structural, systemic changes to protect our global biodiversity (and the Indigenous communities who guard it and call it home). We need to hold our world leaders to their word when they say they care about biodiversity. As individual citizens, our best shot is holding our own political representatives accountable.

The time for doing these things is running out: the fires are blazing as we speak.