Photos of a fast fashion dumping ground in Chile have been circling the internet this week. A new investigative report exposes the exploitative truth behind Shein’s “glitzy front”. As we enter the retail holiday season, we ought to remind ourselves that ultra fast fashion, faster than ever, kills. We need to stop overproduction now. But how do we do that?

Have you ever seen a mountain of discarded clothing in a desert?

This week, a series of photos started circulating around the internet, and it wasn’t pretty. In the driest desert in the world, Chile’s Atacama, piles upon piles of discarded clothing stretch as far as the eye can see. The photos are staggering. One would think that it was an exhibition about modern-day overconsumption. Except, it’s real life. Why, you ask?

According to Al Jazeera’s reporting: “Chile has long been a hub of second-hand and unsold clothing, made in China or Bangladesh and passing through Europe, Asia or the United States before arriving in Chile, where it is resold around Latin America. Some 59,000 tonnes of clothing arrive each year at the Iquique port in the Alto Hospicio free zone in northern Chile. Clothing merchants from the capital Santiago, 1,800km (1,100 miles) to the south, buy some, while much is smuggled out to other Latin American countries. But at least 39,000 tonnes that cannot be sold end up in rubbish dumps in the desert.”

Sounds familiar? That’s because it is. Chile is not the only country in the world that has become an “away” for discarded garments, used and disposed of often by wealthier consumers across the Global North. Parts of other countries, especially across Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Africa, too, have become home to dumping grounds for the excesses of fast fashion. The capital of Ghana, Accra, sees some 15 million used garments every week, according to the OR Foundation. The truth is, we are cycling through clothing faster than these “aways” can handle.

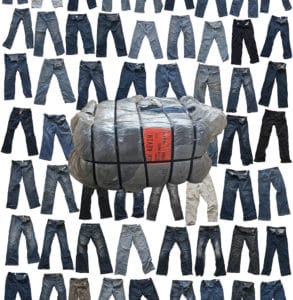

IMAGE: via Dead White Man’s Clothes | IMAGE DESCRIPTION: An edited graphic; a white background with various men’s jeans edited on top of it. The jeans are in various colours, dark blue, light blue, army green, black, etc. On top of the jeans overlayed on the white background, is a bale, called “Kevin”. Read more about the story of Kevin The Jeans Bale from Dead White Man’s Clothes, a project by the OR Foundation, here.

As Liz Ricketts, founder of the OR Foundation, said: “[We are burdening people] with the excesses of the linear economy in the Global North.” This is revealing for two reasons. First, it’s a reminder that these piles of discarded clothing have consequences beyond looking visually alarming. Communities in these dumping grounds are going into debt, and the process is destabilising entire economies. Second, contrary to what you might have heard? Such images, depicting the very real dumping grounds in the Global South, are not a simple result of us individually buying too much.

To be clear, wearing longer and saying no to fast fashion are meaningful actions. Creating a culture of care for our garments is something that needs to happen. Especially in response to the massive dumping that’s happening across borders. But the problem, as Ricketts pointed out, is the “linear economy”. It is the way the take-make-waste system, held up and perpetuated by ultra fast fashion corporations, promotes and thrives upon a culture of excess, of overproduction, and of overconsumerism.

This of course, then leads to consumers in the Global North to subscribe to this culture. Again, saying this doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t embrace our agency in the system. (We are consumers after all, who are responsible for our own decisions.) It is merely emphasising that what we’re dealing with is a problem that requires more than just telling consumers to buy less and buy better.

Buying too much is a natural and necessary result of a capitalistic linear economy

Fashion Revolution reported that a recent investigation from CBC News found that online purchases have a return rate of around 30-40%. That’s up from 10% for in-store buys. Given that online sales are “expected to be the primary platform for consumption” this upcoming retail holiday season, “the return rates will likely skyrocket”. So we know that wealthier consumers in the Global North are voracious consumers of fast fashion. But as established, it’s not as simple as people being addicted to buying and “retail therapy”.

Earlier this year, $800 Shein hauls, the epitome of overconsumption culture, was an emerging trend on TikTok. We asked what was fuelling this rampant, over-the-top consumerism. The answer was a mixture of the following. Brands using algorithms to assess and respond to fashion trends in real-time. Influencer and celebrity culture. And yes, the human impulse to fit in, to stand out, for new stuff, but being amplified by fast fashion brands. That last piece of the puzzle is key. That desire is in some ways “natural”, but it’s also simultaneously manufactured by fast fashion brands.

IMAGE: via Fashion Industry Broadcast | IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A collage of the avant-basic style. From left to right: an image of a cow-print orange pant, with checkered purple socks and yellow platform sandals, stepping on a checkered blue platform. In the middle, a person with black hair in a short, feminine cut, wears a checkered cherry pink sweater, holds a brown and black checkered furry bag, and wears a printed brown and black pant. On the right, a person is wearing a retro blue psychedelic printed second-skin top. They are wearing a retro orange belt, and a printed blue and white flower tight pant.

Brands like Shein use algorithms to manufacture this. Psychedelic prints, pastel cardigans, mules galore: chances are you’ve seen the “Avant Basic” style all over your Instagram Explore page, a term coined by writer Emma Hope Allwood on Twitter in January. Allwood, in a follow-up tweet, actually called it by another name: “algorithm fashion”. In other words, she explained: “quirkiness in the age of mechanical reproduction”.

Brands like Shein probably manufactured the trend (by way of mass-churning out these garments the moment they became popular, gifting them to influencers, having them suddenly pop up everywhere on our feeds). This kind of mass faster-than-fast production is their business model. They thrive on micro-trends that are short-lived, that explode everywhere for five minutes and disappear immediately after. They thrive on the fact that we can never keep up, and that, more importantly, we feel that way too.

This overproduction and overconsumption is necessary for fashion businesses to survive in a cut-throat capitalistic linear economy. It goes from farm to factory to Instagram to dumping ground: over and over again.

The cost of overproduction isn’t just environmental

What’s the true cost of overproduction? A new report from Public Eye looks behind the “glitzy front” of Shein, visiting some of its suppliers in China. As it turns out, unsurprisingly, the corporation that can produce a dress within a week is hiding serious labour exploitation. Public Eye reported: “The researchers located 17 of the 1,000 companies who produce for Shein, including numerous informal workshops with no emergency exits and with barred windows that would have fatal implications in the event of a fire.

The employees, who without exception come from the provinces, graft for 11 to 12 hours a day and have only one day off per month. That makes for 75 hours work a week, which violates not only Shein’s Supplier Code of Conduct, but Chinese labour law, on numerous counts.” At the heart of Shein’s production, amidst its most important suppliers, is such inhumane working conditions.

Public Eye concluded, scathingly: “Shein’s business model is set up to control as much of the value chain as possible, while taking on as little responsibility as possible. Through its combination of a cutting-edge online strategy and archaic working hours, the Chinese newcomer is perfecting the fast fashion industry in a particularly insidious manner.”

This isn’t new

Fast fashion’s exploitative practices aren’t anything we haven’t seen before. It’s just faster than ever, and thus more exploitative than ever. While we haven’t seen a repeat of the Rana Plaza incident for years now, the ongoing violences that are present everywhere, all the time, in our 24/7 globalised supply chain add up. And we shouldn’t need another Rana Plaza to get the fashion industry to wake up.

There’s no easy answer to a systemic problem. It’s not an easy fix. Not conscious collections, not clothes recycling initiatives. It’s not even about boycotting fast fashion. The answer is an entirely reimagined fashion ecosystem. Rethinking supply chains, industries, and rethinking the capitalist mode of consumption and production we’re used to. This retail holiday season, beyond just buying less, buying better? Try thinking about how you can tackle the problem at its roots.

Show solidarity with garment workers. Advocate for wealth tax against rich fashion moguls and billionaires. Raise awareness of the exploitation up and down the supply chain. Anything less, unfortunately, would merely be putting a bandaid over a gaping wound. But in a world where people-powered campaigns are seeing wins, industry shifts, and even sometimes government response? There is hope yet that such deeper, committed action, over time, will work.

The question now is, will you be part of it?