We all know how invaluable trees, and especially rainforests, are for combating climate breakdown but there is another vital element that gets a lot less attention than it deserves – soil. 95% of the world’s food production relies on the soil but industrial agriculture has led to the loss of one-third of the world’s topsoil. While billionaires are busy writing books and creating prizes championing tech solutions for carbon capture, some of the most effective solutions are right under our noses. Or our feet.

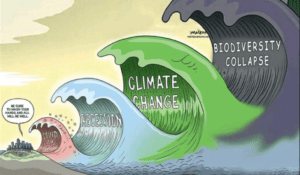

You might be familiar with this meme as we are increasingly hearing from scientists and climate experts biodiversity loss, of which soil degradation is a huge component, has reached the point of global crisis, that many believe is even greater than the climate crisis. Terrifying right? But hope is not lost, because while human’s are facing our greatest challenges, they are so interlinked that we can find solutions that address many of the root causes at the same time.

“The world is facing three major crises today: the loss of biodiversity, climate change and the pandemic,” says biologist Cristián Samper at the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York. “They are all interrelated, with many of the same causes and solutions.”

First some incredible facts about soil;

> Soil is alive – there are more microorganisms in a handful of soil than there are people on earth (about 10 billion).

> About a quarter of all earth’s species live in the soil.

> Soil filters pollutants out of underground water.

> Like the oceans, there is so much more to discover in our soils, with only around 1% of micro-organisms identified.

> Earthworms are soil’s most important resident – they convert organic matter into food for plants, improve the structure and so much more.

Our soil is being eroded at an alarming rate

Because damaged soil is not recoverable within a human lifespan, it is considered a finite resource but according to the Soil Association, we are currently losing the equivalent of 30 football pitches of fertile soil every minute. Healthy soils are formed over thousands of years through weathering and we are wrecking them at warp speed.

The industrial revolution was a game-changer in terms of human innovation. It also marked the beginning of our disconnection from nature. This development and industrialisation accelerated after the second world war ended and the global population and production started to boom. Modern agriculture, our industrialised food system, is one of the primary ways in which humans are having an impact on our environment.

So, how did we get here in such a short time?

When left to its own devices, nature has its own cycle of reciprocation. Every part of the ecosystem benefits from and contributes to the overall balance. Conversely, modern farming techniques interrupt those cycles which has led to widespread soil degradation and become an accelerant to global warming. Two of the most serious drivers of this soil depletion are tilling and pesticides.

Tilling is the process of turning over the top layer of soil to prepare it for planting crops. This removes plant matter and leaves the soil vulnerable to being eroded by wind and rain. With the invention of mechanical farm equipment, farmlands have been over tilled and damaged to the point of desertification – turning from fertile soil into arid desert. Experts estimate that about two-thirds of the world’s land is being desertified.

Because humans have separated livestock and crops in industrial agriculture, we have disrupted natural fertilisation cycles. Without animals to fertilise the soil and crops, we have replaced them with chemical assistance, and in the absence of larger predators, we rely on pesticides to keep bugs from destroying harvests. Despite increasing data that this is damaging farmlands, usage is continuing to rise. In the UK alone, the number of pesticides applied to an average hectare of UK cropland rose by a shocking 24% between 2000 and 2016.

The plight of pesticides

Pesticides don’t just kill the insects that may damage the vegetables, they also wipe out any other microbes, including earthworms, in the soil which further contributes to soil degeneration. This leads to poorer quality crops and in turn less nutrient-dense foods. If that wasn’t bad enough, chemical pesticides have been also linked to a plethora of illnesses in humans. Our food which once sustained us is now making us sick. Monsanto, the world’s largest agribusiness, is involved in multiple legal cases for their usage of toxic herbicide, glyphosate, a suspected carcinogen.

Another big piece of this rather depressing soil depletion puzzle is our over-reliance on a small number of so-called ‘cash crops’. These are crops that farmers know will fetch a guaranteed price and therefore provide more financial security for growers. Rice, maize and wheat account for more than 90% of China’s total food production. In the US just three products make up 70% of crops – corn, soy and hay. And we are not even planting these for human consumption. Vast quantities of these crops, especially soy, is being used to feed livestock that we slaughter for meat.

After the cash crop is harvested, the soil is left arable until it starts to grow again. During this arable phase, the soil has no plant roots to aid carbon and water absorption and is left vulnerable to erosion. For the next seeds to be successful, the soil has to be tilled again and heavily sprayed with fertilisers and pesticides and the cycle of soil degradation continues.

Soil and the climate crisis – the good…

Healthy soil contributes to a balanced climate and desertifying soil accelerates climate change, the two are intrinsically linked. However, many of our climate solutions, like a reduction in the use of fossil fuels, don’t address our soil crisis. This is why scientists are now speaking more and more about soils and bio-diversity, in order to ensure we are not leaving out a crucial part of the earth’s ecosystem in our climate commitments.

Repairing the world’s soil will slow down global warming. Plants take carbon in from the air and use it as energy. 40% of that carbon is sent down into the soil through their root systems. This makes the soil a fantastically effective carbon capture solution and soils actually store more carbon than all the world’s tree and plants combined! Soil in the UK sequesters nearly 10 billion tonnes of carbon, which is equivalent to the total global emissions created by the human population in one year.

Healthy soil can also help to prevent floods by storing water. Further to flood prevention, this means that droughts can be mitigated because the soil is holding water and this is being released through vegetation.

…and the bad

Unfortunately, as we till and erode the soil the carbon is released and the desertification of soils is a major contributing factor to the changing climate. Healthy soil gives life to healthy plants and plant coverage increases humidity in the air. Without thriving plant life, rainfall decreases and we are left with drought, which means even more erosion and degradation of the soil. Without soil, temperature changes are more extreme – hotter in the day and colder at night. During a field’s arable phase, the climate becomes more extreme but when the crops start to grow again, the weather begins to regulate again. It is clear that saving our soil needs to be prioritised as part of any robust climate action plan.

And just when you thought this couldn’t get any worse, soil turning to dust around the world is also exacerbating another disaster – the refugee crisis. Millions of people are driven off their land every year as the soil is destroyed and can no longer grow food to feed the community. The Environmental Justice Foundation shares some devastating statistics on their website, “Extreme weather events – from floods and storms, to heatwaves and drought – are already displacing an estimated 41 people each minute, and as temperatures continue to increase, climate extremes will worsen, sea levels will rise, and the world’s most vulnerable will bear the brunt.” According to their data, 21.5 million displacements each year between 2008 and 2016 have been caused by climate breakdown.

The change we need: regeneration

In the climate emergency, the impact that soil has can either be positive or negative and it is all down to how we farm. Change is on the horizon. Regenerative farming practices are on the rise and on these farms, soil health takes centre stage. The farming practices we currently have in place are extractive, taking as much as possible without giving anything back to the soil. To restore the balance, we need to move to a more harmonious system.

Regenerative Agriculture is based on four key practices;

> Tilling is minimised or stopped completely to allow the soil to settle and repair.

> Cover crops, including trees, are introduced so that soil is protected in between harvests with root systems drawing carbon into the soil to seed micro-organisms.

> Crop diversity creates a habitat for a much wider array of plant and animal species contributing to the health of the soil. Crop rotation also means that harvests can be year-round with seasonal produce.

> Livestock is reintroduced to restore the natural balance by feeding on grass and smaller animals and fertilising the soil.

The shift we need: governments

Farming can be an insecure livelihood and our current systems are not built to support those who have a bad harvest year. Farmers grow cash crops because they are incentivised to by government subsidies. Widespread chemical usage is almost like an insurance policy to ensure they are producing what they need to make a living.

The transition for regenerative agriculture will be difficult for farmers in the short term – they will have to change the way they do everything and many of them will risk losing money at the outset. We need governments to get behind a just transition by supporting farmers to adapt to new ways of working. Soil regeneration after decades of harsh chemical treatment won’t happen overnight and it could take years for the soils to repair. In the interim, they have to be a plan for assisting farmers and recognition that we will all benefit from healthier soil, food and climate.

Of course, we would be remiss to have any conversation about regenerative agriculture without mentioning Indigenous peoples. Although they make up just 5% of the world’s population, Indigenous people protect 80% of our biodiversity.

In an interview on Decolonising Regenerative Agriculture for Bioneers, A-dae Romero-Briones (Cochiti/Kiowa) is the Director of Programs: Agriculture and Food Systems for the First Nations Development Institute said “There are stark differences between agricultural systems in indigenous communities and agricultural systems in contemporary communities. The first being the idea of collective resources. In an indigenous community, there are some things that just cannot be commodified – land, water, air, animals, even the health of the people, all of which are considered collective resources. Collective resources require collective and community management. Contemporary agriculture doesn’t have the same base. In contemporary agriculture, there are individualized, commodified resources like land, you can buy water, at one point in our history you could even buy somebody’s body and health.”

If we are going to reconnect with the earth and soil and find our way back to harmony with the rest of the plants and animals in our ecosystem, we need to preserve Indigenous wisdom.

If like us, you want to nerd out even more on your new favourite topic, we highly recommend checking out the documentary Kiss The Ground.