Asos just paid £330m to Arcadia retail group to buy up Topshop, Topman, and a few other retail brands. Sir Phillip Green, chairman of the Arcadia group, who’s practically a billionaire, is set to earn £50m from the sale. But the 1,000+ garment suppliers in the supply chain will get less than 1% of how much they are owed. Who will #PayUp for the garment workers?

What happens when fast fashion brands meet their end?

At the end of last year, the Arcadia group, which owns Dorothy Perkins, Miss Selfridge, Topshop, and more, collapsed into administration. Just this week, the bidding for the retail group ended, with major online retailer Asos coming out on top. For £330m, Topshop, and all the brands within the group, was sold.

This sale marks the end of an era, in some ways. Many fans of Topshop particularly mourned the loss of the brand that represented their “first foray into adult fashion”. As one millennial writes, in the mid-2000s, Topshop, at the peak of its popularity, collaborated with “titans of fashion and music, from Kate Moss to Beyoncé.” It even had a spot on the London Fashion Week schedule. But somewhere along the way, the “90,000-square-foot Oxford Street emporium that was once the beating heart of London fashion […] became just like any other fast fashion store, peddling unremarkable designs in cheap, disposable fabrics.”

And just like any other fast fashion store, Topshop is unethical through and through. Aside from the fact that its fast-fashion model is inherently exploitative and unsustainable, the brand has also been embroiled in scandal. (Even Beyoncé’s Ivy Park collection wasn’t spared). Unsurprisingly, Topshop’s end (or at least the end to this chapter) is tainted too. For one, since Asos operates exclusively online, it has not bought any of the brand’s 70 stores, putting at risk the jobs of 2,5000 high-street shop workers. Only 300 head office staff will be saved. To top that all off, some of them even found out via online media.

Spare a thought for all the staff that have been made redundant before you start crowing on social media! THEY should have been told first – NOT twitter!

— H (@Hayley1408) February 1, 2021

What about the backbone of the industry?

It gets worse. Not only is the brand not taking responsibility for the jobs of these high-street workers, but they are also failing to #PayUp to protect their garment workers—undoubtedly the backbone of the industry.

As reported by the Guardian, while Sir Phillip Green will receive £50m from the sale of Topshop, the brand’s over 1,000 suppliers will get less than 1% of the money owed to them. (They are owed at least £51m.) It is unclear how much is owed in total to the garment workers further down the supply chain. Though, in April last year, it was revealed that the Arcadia group cancelled over “£100m of existing clothing orders worldwide from suppliers in some of the world’s poorest countries”. Executive editor at US-based labour rights group Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), Scott Nova, said that the effect of these cancellations “is to force suppliers into bankruptcy and to leaves thousands of workers without income”.

According to the WRC, 88% of garment workers report that diminished income has led to a reduction in the amount of food consumed each day by members of their household. COVID-19, of course, has made all this worse. Meanwhile, Sir Phillip Green continues to profit. The man, if you didn’t know, is practically a billionaire. A tax-dodging, pensioner short-changing billionaire who has also been accused of multiple counts of sexual misconduct and racial abuse. So we’re not surprised.

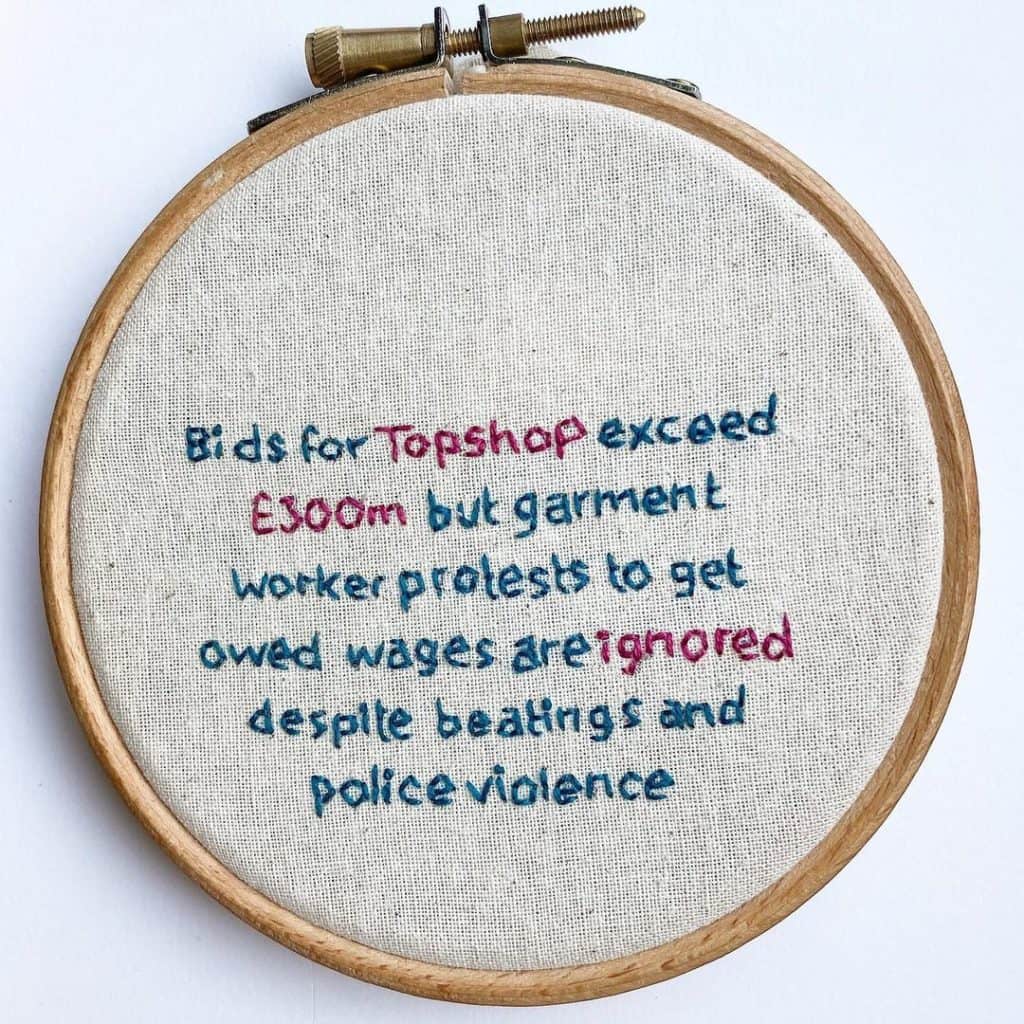

Image via Bryony Porter (@tickover), ID: Hand embroidery hoop on a white background, calico fabric with blue and pink stitched text reading “Bids for Topshop exceed £300m but garment worker protests to get earned wages are ignored despite beatings and police violence.”

Stolen wealth must be returned: where is the justice?

As fast fashion activist Bryony Porter writes: “Arcadia’s actions are crimes against humanity. But real people have made those decisions. Can the mass cancellations of orders, wages and therefore the starvation of workers be called anything else? But the company can be sold and start over under a blank slate. Where is the justice? Every penny of that wealth was made by human hands. It is stolen wealth and belongs to garment workers. It is not good enough.”

This recent episode of injustice is just a continuation of the ongoing trend of fast fashion’s vicious crimes against humanity, against garment workers who often are people of colour. They are the ones who have bled—literally—and sweat to make the clothes we wear. To make the clothes that have contributed to the rise of these retail brands and the increasingly obscene amounts of wealth these billionaire owners have accumulated. Fast fashion, and the fashion industry in general, must reckon with this, instead of starting new chapters on supposed blank slates.

As Orsola de Castro, founder and global creative director of Fashion Revolution writes: “Unless the workers are paid in full, this is how the new Topshop will start [its] journey on [Asos], burdened by the weight and misery of unpaid toil, drenched in chemicals and injustices.”

How can the fashion industry do better?

There are already various groups around the world working towards fighting injustices against garment workers. In April last year, the Clean Clothes Campaign launched the #PayUp campaign. It was launched with the reveal of the fact that global fashion brands have refused to pay over $16 billion since the beginning of the pandemic. For context, stores closed and brands and retailers pushed the risk down the supply chain, cancelling orders placed before the crisis. This left many factories without money to pay wages.

Since the launch of the campaign, many consumers have joined in on the call to global fashion brands to #PayYourWorkers. But the fashion industry continues to ignore calls for justice. While continuing to launch more “conscious” lines. And virtue-signalling via their social media platforms whenever something happens and requires them to pretend to care about social justice. Until today, reports of financial losses, delayed payments, cancelled payments, everywhere, continue to increase. Not to mention, the pandemic isn’t easing up, and the conditions are worsening in many of these cities.

As consumers, if you can afford it, donate to organisations that are fighting for garment worker justice. Support influencers who are actively talking about these issues. Keep the pressure on fashion brands to get them to #PayUp what they owe. And yes, consume better. But don’t forget that fashion activism is ultimately about seeking justice and building a better system. For now, that’s all we can do.