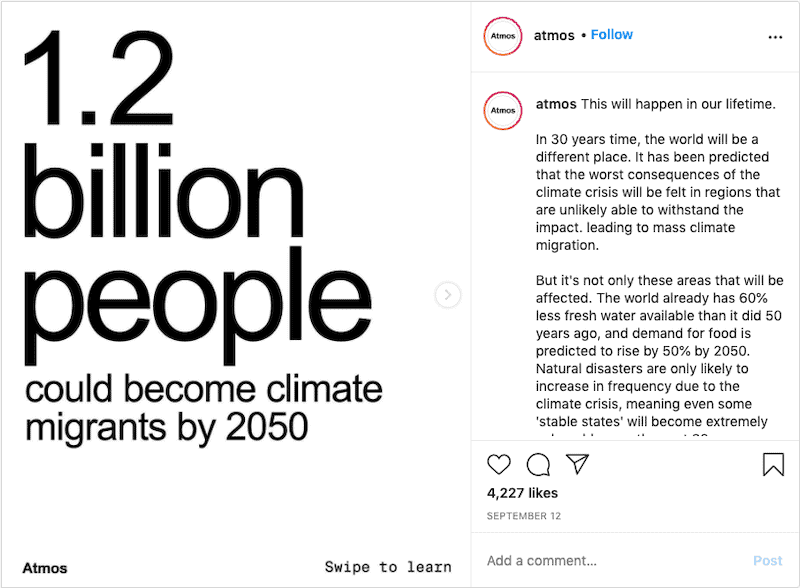

The Ecological Threat Register for 2020 just dropped. And one of its key takeaways is that by 2050 1.2 billion people could become climate migrants. Many of these people will be from countries in the Global South that are already experiencing political and ecological turmoil. So what does this mean for the rest of the world?

In California’s Central Valley, you will find a landscape that contrasts greatly with all of the Big Sur postcards and ultra-green Beverly Hills gardens tucked away in our collective Netflix consciousness. The Valley is the sort of place you can imagine tossing an egg on the ground and watching it fry up before you. Yet despite its raging wildfires, California is an ideal location for work: the agriculture industry is booming. And that is why, when you travel through the Central Valley, what you’ll find is a hot grey strip. Long, flat factory farms line the road. Thickly layered farmworkers bend over dirty looking almond plantations. Under the blazing sun, they spray pesticides all day long.

These workers account for 10% of employment in the United States’ food industry, many of whom are fleeing harsher conditions south of the border. They occupy the crucial roles that nationalised citizens will not fill. These workers are the cogs in the wheel of California’s monster economy.

Firstly, what exactly is a climate migrant?

In 2009, experts predicted that global warming could displace up to 150 million people by 2050. That prediction has now increased nearly ten-fold: current modelling estimates that at least 1.2 billion people will experience life-changing environmental events within the next thirty years. And who’s to say that number won’t increase again? The term “climate migrant” describes the subset of people forced to flee from environmental conditions that render them homeless, out of work, or at risk of both. Think water and food scarcity, rising sea levels, extreme droughts, and ever-expanding “hot zones“. But it is important to note that climate migrants do not qualify for protections that other types of refugees may be eligible for, such as relocation support.

What the Ecological Threat Register tells us

The Ecological Threat Register is an annual measure of population growth, water stress, food insecurity, droughts, floods, cyclones and rising temperature and sea levels. The 2020 report is about as gloomy as you can imagine. One important finding was that countries facing the highest number of environmental threats are also among the world’s “least peaceful”. These countries tend to sit within the regions of North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South and West Asia. The Register also measures an area’s relative “resilience”– the ability to adapt to future shocks. Countries that lack significant resilience will experience “worsening” food insecurity, “competition over resources,” and “increasing civil unrest”. These factors could lead to mass population displacement. This will ultimately have a run on impact for regions such as Australia and Western Europe, who have already proven themselves to be underprepared for recent refugee crises.

Climate migrants have no rights

Under international law, no country is obliged to accept “climate migrants”. On the surface, this is a paperwork problem. Climate migrants are not covered by the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which was created long before widespread climate emergencies even seemed like a possibility. The law was designed to protect persons fleeing persecution, war or violence. So where do climate migrants fit in, and what can they do? The answer is, basically, nothing.

But this short VICE documentary says it best: people migrate to survive. We always have and we always will. In the documentary, Honduran farmer Audelio Mejía explains how the recent unpredictability of weather patterns have impacted his family business. “It used to be that it would rain tomorrow or the day after. Now, the rain just arrives suddenly or drought comes” he tells the cameraman. He and his workers face a decision. They either dig in and stay where they are, risking an uncertain future and even more significant harvest losses. Or they pay the price for a risky journey to California, where they may well have to give up their human rights.

Disappearing countries

You might be wondering, what happens to the countries that people are fleeing from? Take a look at Tuvalu: a tiny island nation in the South Pacific. Slowly sinking each year, inhabitants describe disappearing beaches and increasingly muggy weather. Studies show that due to Tuvalu’s remote location, high levels of skilled emigration and “limited opportunities for lower-skilled migration”, the country is facing significant and severe unemployment. Many young people will move to places like New Zealand for work, where they join a migrant population that doubles every five years. Basically, islands like Tuvalu are crying out for innovative, sustainable solutions to protect against destructive weather events. But soon no one will be left on the island to save it.

Are we running out of time?

This interactive map from NASA demonstrates sobering visual data that sheds light on how these estimates have increased so dramatically in such a short space of time.

It seems like everyone is talking about ‘the point of no return’, climate-wise. But we do have options, they’re just not cheap. So, for the same reasons that the Californian economy keeps running unsustainable agricultural practices, the world is hesitant to “go green”. For example, the IPCC reports that to “keep warming under 2°C by 2100”, net carbon emissions need to be “phased out completely” by 2070. To do so, a total shift to renewable energy is in order, which could indefinitely cost 2-2.5% of global GDP every year.

The good news is, according to the UN, that such investments “would deliver longterm economic growth as high as presently projected but with far fewer impacts from climate change, water scarcity and loss of ecosystems.” In effect, some governments are starting to warm up to the idea of a green future.

Shifting the focus

So a glimmer of change might be on the horizon. But the problem is, the people the climate crisis hurts the most get seen the least. As I write this article, images of a glowing orange sky over popular landmarks in cities like San Francisco adorn the front pages of most major news outlets. While focusing on horrific events that are impacting “Global Northerners” might convince some people that climate change is real, their overwhelming spotlight mystifies the core of the problem: the actions of the Global North unequivocally harm and dislocate the Global South.

#LittleGreenSteps

The easiest and fastest way to make a change is by expanding your awareness of a subject. Netflix is currently streaming the sobering and informative series Immigration Nation, which explains the reality of climate migration; it’s well worth a watch. If you have the resources, there are plenty of great foundations doing work for climate migration, such as the Climate Migrants Project and the EJ foundation. For now, I’ll leave you with the words of Sir David Attenborough. In his recent documentary Climate Change – The Facts he comments that “While Earth has survived radical climactic changes and regenerated following mass extinctions, it’s not the destruction of Earth that we are facing, it’s the destruction of our familiar, natural world and our uniquely rich human culture”.