Two new reports and a documentary sound the alarm on biodiversity loss this week. But are you paying attention? Do you know why it matters? And what the hell can we do now? Is there even hope?

UN: the world is failing on its biodiversity targets

A decade lost

It’s October 2010, in Japan. Environment ministers from almost 200 nations have gathered in a conference hall in Nagoya. A typhoon is looming outside, while the ministers inside are cheering. Why? They’ve agreed to adopt a new UN strategy that aims to “stem the worst loss of life on Earth since the demise of the dinosaurs”, also known as the Aichi targets. Each signatory will draw up and execute national biodiversity plans. Collectively, these plans are supposed to halt overfishing, control invasive species, reduce pollution, minimise the pressure on coral reefs, and half the loss of genetic diversity in agricultural ecosystems. “There is a momentum here which we cannot afford to lose,” says IUCN’s director of conservation policy, Jane Smart. “In fact we have to build on it if we stand any chance of success in halting the extinction crisis.”

Today, it’s September 2020. It’s been almost a decade, and by now, we’re supposed to have met the Aichi targets, which were set for 2020. The UN just released a new report, titled the “Global Biodiversity Outlook 5”. Its innocuous name belies a devastating truth. The world has failed to meet a single Aichi target, making this the second consecutive decade that governments have failed to meet biodiversity targets.

What’s happening instead?

Governments are actively funding subsidies harmful to biodiversity. Overall global demand for resources is increasing, and the impacts of their use remain well above safe ecological limits. Loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitats remains high in forest and other biomes. Wilderness areas and global wetlands continue to decline. Marine fish stocks are more and more overfished, while fisheries and fishing practices are still damaging marine life. Food and agricultural production, and pollution (including from excess nutrients, pesticides, plastics and other waste) remain as main drivers of global biodiversity loss. Multiple threats continue to affect coral reefs and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change and ocean acidification. Species continue to move, on average, closer to extinction.

And this is just a snapshot of the report. Crucially, the UN’s biodiversity head Elizabeth Maruma Mrema highlights: “Earth’s living systems as a whole are being compromised. And the more humanity exploits nature in unsustainable ways […], the more we undermine our own wellbeing, security and prosperity.” Indeed, the capacity of ecosystems to provide the essential services on which whole societies depend continues to decline.

Who suffers? The report points out that poor and vulnerable communities, and women, are disproportionately affected by this. Even though, of course, these communities tend to do the least harm. And sometimes, especially in the case of Indigenous communities, they also know much more than we think. In fact, by the way, the report mentions that traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use have not been sufficiently incorporated and that Indigenous peoples and local communities are also not substantially participating in associated processes. But more on that later.

For now, on to the second report this week.

WWF: wildlife populations are in freefall around the world, driven by human activities

Zooming in

WWF’s Living Planet Index (LPI), which is one indicator among many other biodiversity indicators out there, zooms in on the population abundance of thousands of vertebrate species around the world. It tells us that between 1970 and 2016, global populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians, on average, plunged by 68%. What exactly this implies about populations, species or individuals, or how exactly this number is calculated, you can read about in the full report. For our purposes, all you need to know is that species population trends are important because they indicate overall ecosystem health.

And what does this 68% imply? Taken along with the vast majority of other indicators that show net declines over recent decades (see: the IUCN Red List Index, Species Habitat Index and Biodiversity Intactness Index), it tells us that our natural world, as the report writes, “is transforming more rapidly than ever before”. Why? “That’s because in the last 50 years our world has been transformed by an explosion in global trade, consumption and human population growth, as well as an enormous move towards urbanisation. Until 1970, humanity’s Ecological Footprint was smaller than the Earth’s rate of regeneration. To feed and fuel our 21st century lifestyles, we are overusing the Earth’s biocapacity by at least 56%.”

The new geological age

All these underlying trends point to how humans have changed the world irreversibly in the last few decades. In a collection of essays accompanying the report, Sir David Attenborough notes that we’ve entered what some call the Anthropocene: “the Age when humans dominated the earth”. Instead of recognising that we’re but one of the (maybe) 8.7 million species that walk the earth, we’ve come to see ourselves as the centre. This sort of thinking, by the way, is what some call “ego-centric” rather than “eco-centric”. And it’s the sort of thinking that might just be our downfall.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CFaukEPBs_d/

Sir David Attenborough is hopeful. “The Anthropocene,” he suggests, “could be the moment we achieve a balance with the rest of the natural world and become stewards of our planet.” But before we can imagine a world where humans manage to stop biodiversity loss, we need to wake the hell up to the facts. Which, coincidentally, is the name of his new documentary.

“Extinction: The Facts”

Not your average David Attenborough doc

Sir David Attenborough’s new documentary (which you can watch for free here) is surprisingly radical. It departs from his usual style, and addresses, like the title implies, the harsh truths. For example, it shows footage from the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, where Severn Suzuki shows up at the UN “to tell you adults that you must change your ways”, and then cuts to Greta Thunberg’s high-profile “how dare you” speech, also to the UN, to show how little progress has been made.

Like the two reports mentioned above, this documentary is yet another reminder that we’ve not shifted from our nature-destroying trajectory, even though we’ve been told the same message so many times before. (See: when we were warned that Earth’s sixth mass extinction is underway three years ago. And when we were told that a million species are at risk of extinction just last year.)

Will this time be different?

Maybe reminding humans of why biodiversity matters will make things different. Some things are more obvious. Like the fact that without plants, we wouldn’t have oxygen, and without bees, we wouldn’t have fruits or nuts. Others are less obvious. Coral reefs and mangrove swamps protect coastal communities from natural disasters, and trees absorb air pollution in urban areas. But more importantly, these seemingly disparate elements join to form whole ecosystems, which is a point the documentary attempts to drive home.

“We tend to think,” says Kathy Willis, professor of biodiversity at the University of Oxford, “we are somehow outside of that system. But we are part of it, and totally reliant upon on it.” The documentary, of course, hammers this in by making the link between biodiversity loss and emerging diseases. It highlights, for example, wildlife trade and removing large predators. These are just two ways in which humans are changing biodiversity, making pandemics more likely.

What now?

Bending the curve of biodiversity loss

Is Sir David Attenborough right to be hopeful? Perhaps. Both the UN and WWF report converge on this point too. The UN report concludes that “despite the failure to met the goals of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, it is not too late to slow, halt and eventually reverse current trends in the decline of biodiversity.” We can turn things around, or “bend the curve” of biodiversity decline, as it has been termed.

But we need “ambitious, integrated action combining conservation and restoration efforts with a transformation of the food system”. This means increasing protected areas, restoring degraded land and integrating conservation objectives into land use planning efforts, while simultaneously changing food production and consumption patterns. These have to happen simultaneously to bend the biodiversity loss curve upward by 2050 or earlier.

Ancient knowledge, new narratives

What both reports mention briefly but fail to centre, however, is the importance of protecting Indigenous cultures to save the world’s biodiversity. As alluded to earlier, Indigenous peoples have conserved biodiversity for millennia. In fact, up to 80% of the world’s biodiversity is located on Indigenous lands. And they’re protecting it better than we have: research has shown that biodiversity is declining less rapidly on Indigenous lands than in other areas. Traditional ecological knowledge is effective in conservation, because living in harmony in nature is, well, natural to them. So no more saying that “humans are destroying the planet”—not all humans are. And we need to learn from these humans who carry centuries of ancient knowledge and centre their perspectives.

Looking back towards ancient knowledge is one thing, but we also need to be able to create new narratives. William Defebaugh, Editor-in-Chief for Atmos rightly notes that we humans are oddly fascinated with stories of collapse. Biodiversity loss is one of those stories. But, as Defebaugh writes, “[w]hen we examine the timeline of mass extinctions throughout history, we see that life invariably begets death, making way for new life. We can understand them as opposite ends of a wheel that are always seeking one another, making that wheel turn—but they are by definition part of the same wheel.”

What stories will we write?

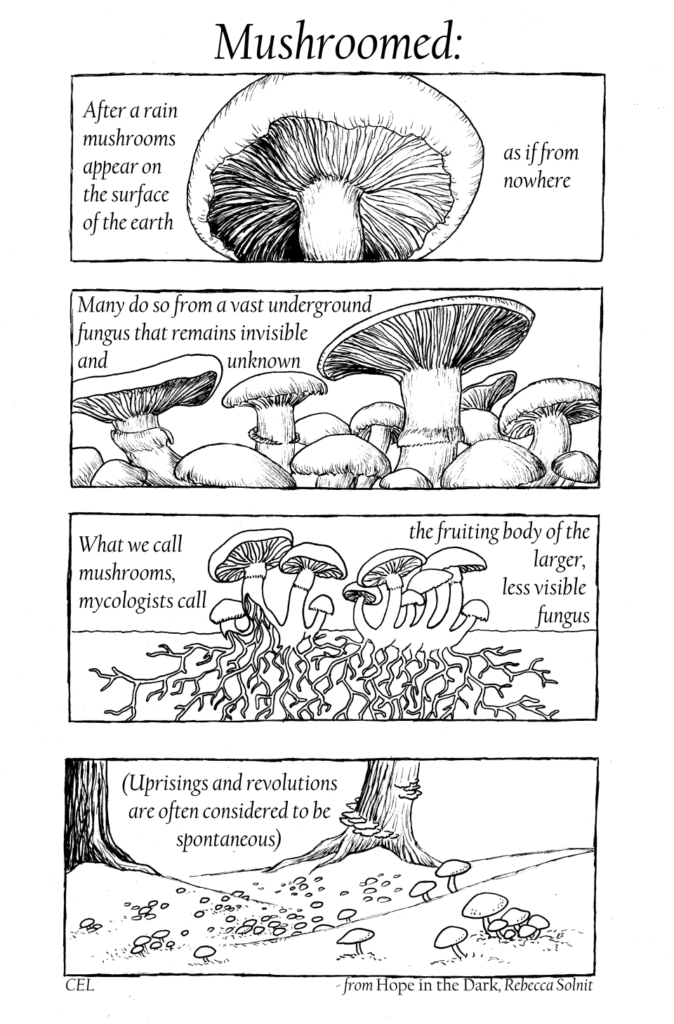

The truth is, stories of Flourish (uprisings and revolutions) are happening everywhere. Within Indigenous communities, between the walls of classrooms, on the streets during protests. Probably even in your local gardens. We’re writing these stories alongside stories of Collapse (biodiversity loss). “We have to be brave and make space for the stories of Collapse as well as Flourish,” Defebaugh writes. “[A]s they have both been part of nature’s story since the beginning. Therefore, they are also our story, the one that we are authoring right now. And stories are the best hope we have.”

The question is: will we be able to hold space for both types of stories? Or will we only resign to stories of collapse, failing to author stories that can change the course of human history?