Just so we’re clear, this is not another generational halfie’s (that’s half-Millennial, half-Gen Z) long-form complaint about social media. Instead, this is a—former/semi-retired?—social media activist whose six-month-long break off Instagram produced some actually useful insights. In other words, if you find yourself worn out by digital activism in this hyper-connected, 24/7 information age, you’re not alone. How do we find some respite, while still being committed to doing the work?

“The Instagram Infographic Industrial Complex”

Or as I like to call it, the Instagramification of activism. If you’ve been on Instagram recently, this would not be unfamiliar. Aesthetically-pleasing multiple-image posts or slideshows, usually starting with a simple block of text that opens with “Why you should care about…” or “Here’s what you can do about…” or “Everything you need to know about…” and ending with a list of resources to learn or do more. In fact, you would’ve started to see it dominate your Instagram feed right around the 2020 resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. Although, both—that is, this style of activism, and the Black Lives Matter movement—have been around for longer than that.

Point is, these have become exceedingly popular. These days, every major social justice issue prompts a new wave of such posts. Anything from the Myanmar coup to the Indian farmers’ protests, from the #StopAsianHate campaign to the problematisation of #Girlboss feminism during International Women’s Day… you name it, there’s probably a post about it.

As this video, titled “the instagram infographic industrial complex” argues: often, such activism is well-intentioned. And certainly, the reach of these infographics to previously unaware audiences is laudable. But there are a few problems with this approach. For one, it makes activism performative. Especially for influencers with massive platforms who now feel the need to be activists (but sometimes only to stay in the good graces of their followers). More worryingly, corporations get on this bandwagon too, co-opting these political messages, and commercialising them. And in the same way, they too desire a continued following (except what they’re after is not your attention, but your money). Most disturbingly, however, the complex forces activism into palatable, 1080px by 1080px squares. This is not to say that these infographics are bad, but that the medium makes it such that creators are forced to optimise them for our consumption, in a world of endless scroll.

This affects us too: shortening our attention spans, forcing us to lose our ability to consume anything more than bite-sized bold text slapped on plain backgrounds. “The intent, identity of the creator, and accuracy of these guides matter a great deal, but more often than not, that nuance is lost on the average Instagram user,” Nguyen writes for Vox, “flattened into a quick share or repost with a hasty tag as they scroll on and on.”

Slacktivism, clicktivism, armchair activism?

A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. Which is to say: call it what you want. It’s the same thing. We can’t be sure whether people are doing anything beyond the screen or not. And as a result, this kind of Instagram activism can dilute activism.

“This… watering-down process,” Cierra Bettens writes for Lithium Magazine, “has led to what some have called the “memeification” of Breonna Taylor’s death. Adding “arrest the cops that killed Breonna Taylor” to unrelated TikToks, selfie captions, and Twitter threads may be well-intended, but in reality, undermines the substance of these statements. To have the death of an innocent Black woman in the hands of the police be limited to a series of memes is more than insulting; it is counterintuitive to the cause itself.” To be clear, this is certainly the worst of social media activism. Not all activism is like this, and there can be much better forms of activism—as shown below.

The more important point here is this… “Revolutionary or not, movements cannot be sustained solely on social media. The history of social movements makes it clear that offline, direct action is what leads to tangible change.” But (and this is a big but), in defence of these Instagram posts, as a maker of them myself once: creators do try to encourage their audiences to take it offline. (We will revisit this idea in a moment).

It’s not all bad

Aja Barber, writer and fashion consultant, made an excellent point on her Patreon recently too. She talked about the (online) #PayUp campaign that succeeded in winning $22 billion against wage theft on garment workers. “As much of the world has been on lockdown this year a lot of campaigning has been in online spaces. So next time someone says that what people do behind keyboards makes them “keyboard warriors”,” she wrote, “remind them that is patently untrue and they’re being ableist AF. Both direct action and putting pressure on brands works.”

The #PayUp campaign is certainly worlds away from the Instagram posts, though. Supporting the campaign by putting direct pressure via online spaces collectively was an entirely planned movement. Liking and sharing an infographic is different. Not to mention…

We need to talk about our shorter attention spans, enabled by social media platforms

Here’s the second reason why Instagram activism is problematic. It speeds up our consumption of activism. And it should scare us that our attention span for issues that pop up on our feeds is as short as our momentary obsession with memes. It’s a running joke that memes only last for something like two days on social media. It’s not a joke that issues trend for the same. And in the same way that Instagram activism has sped up our consumption, Netflix documentaries have done the same. These days, a Netflix documentary, just like a Netflix show, blows up, and everyone has to watch it. Then everyone has to have an opinion about it (guilty-as-charged), almost immediately.

Instead of encouraging nuanced opinions and critical thinking, the landscape becomes flattened to for or against the documentary. And debates are limited to comment sections. Not to mention, the talk about it all fades away after a week. And we’re left waiting for the next issue or documentary to consume. All this begs the question: who wins? Consumers of this hyper-fast, information-overload activism have a shorter attention span. And activists trying to get their audiences to care are competing for their attention. In the end, it’s the social media platforms that win. They’re in it to make money: whatever it takes to get people clicking, watching, using their platforms. It keeps people hooked.

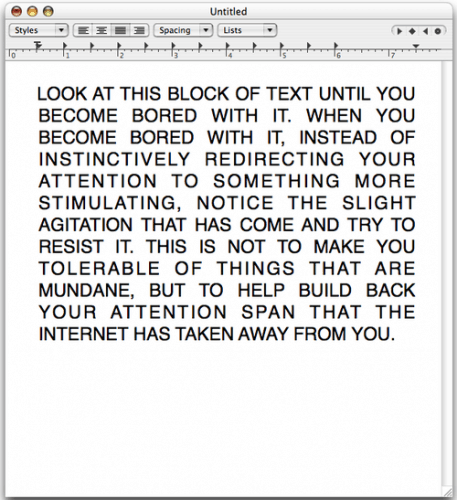

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A graphic of an untitled .txt file, with text in all caps: “Look at this block of text until you become bored with it. When you become bored with it, instead of instinctively redirecting your attention to something more stimulating, notice the slight agitation that has come and try to resist it. This is not to make you tolerable of things that are mundane, but to help build back your attention span that that internet has taken away from you.”

This is not The Social Dilemma

This is to say, this is not an attempt to convince you to ditch social media. It’s not even an attempt to get you to take a break. Social media activism is important. It’s undeniable that these issues need attention. Not least because it gets the issue out to people who have the resources, financial or otherwise, to help. But also because sometimes, such as the ongoing Myanmar coup, the issue does just need international attention. But we have to remember that these social media platforms force us to try to stay on top of algorithms, and inevitably make issues compete for attention, in a way that eventually just burns us, as consumers of these issues just trying to make sense of the world and do something.

The overall effect is the message gets diluted, and we can’t hold nuance. We can’t hold multiple issues at once. And we become obsessed with the information, the symptoms of the problem rather than the problem itself. That is, we fail to grapple with the roots of the issue at hand. (And on top of all that, as author and activist Adrienne Maree Brown points out, it might just be the reason behind the rise of “cancel culture”, which gets in the way of transformative justice. “They,” she says, speaking about these platforms, “were designed to serve capitalism, which means they want as many clicks and likes and as much engagement as possible. And what gets a lot of engagement is drama.” (But I digress—cancel culture is another issue that needs its own nuanced critique, and that’s for another time).

The point is, we are being affected by these platforms. And it’s all worsened by the pandemic: we’re on our screens all the time, and we’re isolated. This means that we don’t have our communities to process these issues with, and all of the emotions they trigger.

What now?

I often think back to this quote I chanced upon from Wendell Barry, in his 1934 essay titled An Entrance to the Woods. “The faster one goes,” he wrote, “the more strain there is on the senses, the more they fail to take in, the more confusion they must tolerate or gloss over – and the longer it takes to bring the mind to stop in the presence of anything.”

The first thing we must do is, admittedly rather clichéd: is mindfully use the social media platforms we’re on. That means checking in with our state of mind before using these platforms. Being intentional about what we’re consuming. This is not to say that every experience with said platforms must be intellectual; the usage of social media can be frivolous, vain, materialistic! There is so much art to be consumed on social media, in the form of selfies, fashion, illustrations, photography, video logs, journal entries and more. But to say that the mindless, endless scroll should probably be limited. A social media clean-up might help, and social media follow-ups too: i.e. reading beyond the screen. (Or beyond the Instagram post, and beyond the documentary).

The second thing, I think, is cutting back to grow stronger. I’m referencing this particular conservatory sign that reads “I Am Not Dead, I’m Dormant: Sometimes you have to cut back to grow stronger. This Namibian grape tree has been pruned to promote future growth and rejuvenation. Watch for new leaves to appear in spring!” And cutting back doesn’t mean cutting back on social media use. But that means when we do consume it, to take sufficient, restful time to heal from the trauma porn that’s everywhere on the Internet. This is absolutely a luxury and a privilege to have, but in order to do the work, we have to ourselves be healed enough to do it. You can’t pour from an empty vessel or a dried-out well.

A different kind of activism

How do we do the work? What is the work? Of course, we still need to accumulate knowledge and information. And we need to keep up with what’s going on in the world. But while doing that, we should also be creating communities that can help us process what we’re learning. We need to be coming together, forming networks that allow us to exchange and engage with information meaningfully. And we’ll need time alone too, off the screen, reading actual books—there’s a wealth of information out there already, if only we tap into it. This collective, and individual, processing will help us realise that the root of all the issues is oftentimes the same, just masking differently.

Coming together with the collective is key here. It’s a realisation that I came to when I came across Lenéa Sims‘ Inner Play, Outer Work approach to activism. She advocates for community-based, sustainable activism. Sustainable, as in, doable in the long term. How is activism made sustainable through her approach? She combines healing activities (Inner Play) with active anti-racism work (Outer Work), all on top of firmly cementing individuals who join her into a community. Having such a community reminds us that we need to do the work ourselves, but we can do the work together, and for each other. (Indeed, caring for each other is revolutionary too: care work can be the work).

It also helps us hold each other accountable: instead of issue cycles, where we get “woke”, do some performative activism, and call it a day (see: that’s enough activism for a day meme), we’ll start seeing cycles of liberation. Indeed, as this cycle of liberation requires: we need to learn how to do the work of maintaining. How do we build and maintain communities that will sustain our activism beyond the screen and beyond the moment?

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A graphic explaining the Cycle of Liberation developed by Bobbie Harro, as further explained here

Parting shots

In all fairness, many activists who are creating these Instagram infographics are already doing this. At least, I can speak for activists like @brown_girlgreen, @queerbrownvegan, @yemagz and the folks behind @theslowfactory. They’re creating communities online, making information and content accessible, and certainly encouraging digestion beyond a single post. I can’t, however, speak for the accounts like @impact, @soyouwanttotalkabout and @theslactivists. And the many more that just pop up after having gone viral. So what then? For posts like these, and for all those Netflix documentaries: find your community. Create a community that can process together with you, ask meaningful questions with you, and do activism beyond the screen with you. That’s how we can start to do better: for each other and with each other. The work can and should start now.