During the pandemic, you’ve probably heard “humans are the virus” or “nature is healing”. If you felt uneasy but weren’t entirely sure why you are not alone. These are examples of ‘ecofascism’. Let’s delve into the roots of ecofascism, bust the overpopulation myth, take a look at how racist and classist ideologies have seeped into environmental spaces and what we can do about it.

What is ‘ecofasism’?

Ecofascism is rooted in *surprised gasp* fascism – an ideology, usually on the far right or far left that restricts the freedom of individuals or groups of people. In environmentalism, it manifests in climate targets or conservation plans that sacrifice certain groups’ safety, wellbeing or even their life in the name of protecting the planet.

It’s easy to assume that defending nature and animals is synonymous with caring about people but racism, classism and ableism that exist in society also show up in environmentalism. Ecofascism is what you get when white supremacy and environmentalism collide.

The Overpopulation Myth

The most obvious example of ecofascism is that of the Overpopulation Myth. First, we’re going to break down what this school of thought is and then we will examine why it’s inaccurate.

Many people still subscribe to the hypothesis that climate change was caused by, and is being accelerated by, the growing human population and that controlling the population will solve the climate crisis. What makes it especially insidious is that the voices that push the narrative are often intelligent, rational people, even revered and we trust what they tell us. Today, the idea that the global population is the root of climate change is perpetuated by high profile environmentalists like beloved broadcaster David Attenborough and legendary primatologist Jane Goodall. Both are patrons of a UK charity that “considers population growth as a major contributor to environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, resource depletion and climate change.”

It’s undeniable that Goodall and Attenborough have contributed positively to the protection of nature throughout their careers and certainly played a key role in public understanding of and attitudes the natural world. However, we would be remiss not to critique their stance on overpopulation and question their statements in reference to it.

Attenborough, 95, once incorrectly attributed famines in Ethiopia to “too many people for too little land”, and insinuated that food aid would be counter-productive. Goodall, 87, spoke at Davos in 2020 about her belief that “All these [environmental] things we talk about wouldn’t be a problem if there was the size of the population that there was 500 years ago.”

But, how will we feed everyone?

A common argument when talking about the world’s population is that we will be unable to produce enough food to sustain everyone. It is not baseless to worry that as the population grows feeding everyone will become increasingly challenging. The nuance I ask you to consider is this – one-third of the food we produce annually is wasted. Much of it actually ends up in landfill where it creates a greenhouse gas potentially 20 times more harmful than carbon, called methane. We will revisit this later but safe to say, we produce an abundance of food already and by tweaking the system we can do it more sustainably, reduce methane in the atmosphere and ensure no one goes hungry.

There are currently 7.7 billion people on earth but each of those people is living very different lifestyles. It is widely understood that the people who have contributed least to climate breakdown are the worst affected and that consequences of global warming disproportionately affect people in the Global South, especially women.

Who is really responsible for global CO2 emissions?

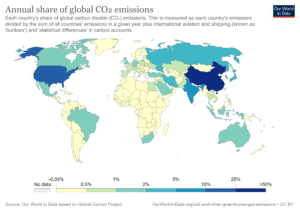

The idea that overpopulation is the driving factor for climate change relies on the assumption that every individual person on earth has the same impact on carbon emissions, therefore more people means more emissions. If that were true, then you would expect those nations with the highest populations would also have the highest emissions. Let’s take a look.

The largest emitters are currently China, the US, India, Russia and Japan. The nations with the largest populations are China, India, the US, Indonesia and Pakistan. With China, India and the US featured in both lists, you might draw a conclusion that a bigger population does in fact mean more emissions.

However, when you look at the ‘per capita’ emissions, you get a very different story.

The top five countries with the highest per capita emissions are Saudi Arabia, the US, Canada, Australia and South Korea. This reveals that the size of a countries population does not determine its carbon emissions. So, what does? “Prosperity is a primary driver of CO2 emissions, but clearly policy and technological choices make a difference.” – Our World In Data

Emissions per capita are generally much higher in wealthier nations. Oxfam reports in “Extreme Carbon Inequality” that a person in the richest 1% of the world’s population uses 175 times more carbon than some in the poorest 10%. As well as citizens in more prosperous nations generally living higher carbon lifestyles, the country’s systems, like energy and transport, are usually powered by fossil fuels. It takes the average Briton just two weeks to create the same emissions it would take someone in Rwanda in a year. And disparities don’t just exist between the wealthier and poorer states, they also exist between classes. This report shows that 1% of people cause 50% of global aviation emissions and highlights that a four-hour flight on a private jet emits the same CO2 as it takes the average European a year to produce.

So, why is the idea of overpopulation so popular?

Like many of the systems and ideologies we have today, the preoccupation with population growth is a product of white supremacy and colonisation. Blaming the climate crisis on population also allows those living high carbon lifestyles to deflect from their own contribution and point the finger at others.

The idea the population growth was linked to social ills has a long and pretty grisly history. Thomas Malthus, an 18th-century English cleric, has often been credited as “the father” of this theory. Malthus claimed humans will always outrun resources available and believed that in order to restore balance, we need natural or artificial population control like wars, famine or diseases. Malthus sparked tyrannical policies that resulted in the starvation of millions in India and Ireland. The primary concerns of his time different from today’s challenges however, according to his Wikipedia page “on the whole it may be said that Malthus’s revolutionary ideas in the sphere of population growth remain relevant to economic thought even today and continue to make economists ponder about the future.” Despite our changing world, there are people who still subscribe to Malthusian theory.

This narrative still plays out in both “developed” and previously colonised countries where poorer communities are harshly judged for having children they “can’t afford” while poverty wages, war, corruption and resource extraction by the rich go unexamined.

In the 1960s and ’70s, this doctrine continued. Influenced by Malthus, Paul Elrich published ‘The Population Bomb’ in which he posited the absolute danger of allowing the human population to grow. Accounting his experience in Dehli, India, Elrich wrote “The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrust their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. . . . [S]ince that night, I’ve known the feel of overpopulation.”

At the time of his trip, Delhi had a population of around 2.8 million. Paris, on the other hand, was home to 8 million residents. Elrich spent time in both cities but only considered Dehli to be overcrowded despite Paris having almost three times as many people. In reality, the overcrowding that Elrich saw was the result of poverty. His suggestion to deal with the overpopulation ‘problem’? Widespread sterilisation of the lower classes.

As George Monbiot, activist and writer via The Guardian, shared “The colonial powers justified their atrocities by fomenting a moral panic about “barbaric”, “degenerate” people “outbreeding” the “superior races”. These claims have been revived today by the far right, who promote conspiracy theories about “white replacement” and “white genocide”. When affluent white people wrongly transfer the blame for their environmental impacts to the birthrate of much poorer brown and black people, their finger-pointing reinforces these narratives. It is inherently racist.”

Who decides how the population is reduced?

Population reduction can happen in several ways – famine, war, extreme weather events, disease/pandemics and reproductive control. Population control often comes with the idea that the mass death of humans is justified and necessary for the survival of the planet. The majority of COVID-19 deaths have been people more vulnerable to the virus in some way; they had to go out to work instead of working from home or work in a people-facing role, they lived in crowded accommodation, they had underlying health conditions as a consequence of poverty.

IMAGE: via Dominic Cummings | IMAGE DESCRIPTION: a clip from a whiteboard with a lot of brainstorming/notes highlighting the quesion “who do we not save”

This photo of a whiteboard from a UK government meeting about the pandemic was recently released to the public by Dominic Cummings, former chief adviser to the British Prime Minister. On the board, you can see the chilling question “Who do we not save?” Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, was also quoted as saying “let the bodies pile high in their thousands.” While this example is not an environmental one, it does illustrate how governments can callously decide that some individuals or groups are less worthy of protection. This same question could be asked by governments when dealing with extreme weather events like bush fires and hurricanes. While so many governments lack diversity, equity and inclusion, this means that primarily wealthy men are deciding the fate of everyone else.

Controlling reproduction

Most forms of contraception are designed for women and so controlling reproduction more often than not means controlling women. Before even delving into examples, we can already see that there is a problem here with power dynamics and inequality. The door is left wide open for oppression and abuse and previous population control efforts have resulted in devastating human rights violations of women around the world. Programmes deployed by Global North to curb population in the Global South have invariably been forcibly implemented, coercive and medically negligent.

In the late 90s, over 300,000 people sterilised were sterilised in Peru without consent. The story was covered in a harrowing documentary by The Guardian. The BBC reported a disturbing instance in a ‘sterilization camp’ in India where a surgeon performed around 80 surgeries with a single instrument, without so much as changing his gloves. Women in post-op recovery laid on the floor of the hospital. 13 died, of suspected septicaemia.

Ecofascism manifests in other ways, too

While the overpopulation myth has clear links to colonial scholars and theories, it can show up in other ways too. Some organisations and philanthropists who invest in environmental conservation and protection are not always benevolent and their biases and prejudice can creep into the work. Essentially, ecofascism, in this context, is the protection of land and/or animals but with a human cost. The people experiencing the harm typically belong to groups that are under-represented in positions of power and their stories go unheard by the general public.

Conservation

The world of conservation is fraught with accusations of human rights abuses and unethical practices under the guise of environmental preservation. Survival International, a human rights organisation that protects Indigenous people has been vocal about violence inflicted on tribal people around the world. They say that current conservation alienates local people rather than forming real partnerships with tribes who have been stewarding the land for generations.

UNESCO shares “Indigenous knowledge operates at a much finer spatial and temporal scale than science and includes understandings of how to cope with and adapt to environmental variability and trends.” Despite accounting for just 5% of the world’s population, Indigenous people protect around 80% of the world’s biodiversity and have been campaigning for the protection of the planet for generations.

Tree planting schemes

Planting trees is a popular method of ‘offsetting’ an organisation or individual’s carbon footprint. Sounds great, right? In theory, yes. However, in practice, tree planting schemes can lead to exploitation of local people and there have been several reports of clearing Indigenous land to make way for planting trees.

Asking “but what about China and India?”

As we already covered, China and India may feature in the top emitters but when you look at per capita emissions, they are much further down the list. China and India are not even in the top 10 despite their population size and status as middle-income countries. So, how is that possible? Many of China and India’s emissions are generated by the good they produce. These goods are then exported to countries like the US, the UK, Canada and Australia. A nation’s emissions are calculated on production rather than consumption basis. If our insatiable need for ‘stuff’ in the Global North was curbed, emissions in India and China would significantly decrease.

Exclusionary activist groups

Representation is vital for decision making but groups who are disproportionately impacted by climate change are often not given a seat at the table. A study shared earlier this year revealed that 97% of employees in the UK environmental sector identify as white. It also reported that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic who work or have worked in the sector faced “jaw-dropping levels of racism” in the workplace. Not only is it shameful for a sector whose mission is to protect the earth to be complicit in shocking racism, but it also highlights a seriously problematic power dynamic.

Many influential organisations are headquartered in the UK and the work they do will have a knock-on effect. When we consider Black communities in the US and UK are more likely to be exposed to air pollution and suffer from respiratory illnesses it is imperative that those communities are included in decision making. It’s not just race, the sector also has a troubling gender gap. Women are 14 times more likely to die during climate-related catastrophes but comprise just 15% of leadership positions at COP.

Mass Shootings

Two mass shootings in recent years, in El Paso USA and Christchurch New Zealand, have been attributed to ecofascism. In both instances, the shooters held beliefs around overpopulation and migration causing environmental breakdown.

“The key thing to understand here is that ecofascism is more an expression of white supremacy than it is an expression of environmentalism.” – Michelle Chan, Friends of the Earth International

In fact, this is what the FBI describes as ‘ecoterrorism’– “the use or threatened use of violence of a criminal nature against innocent victims or property by an environmentally-oriented, subnational group for environmental-political reasons, or aimed at an audience beyond the target, often of a symbolic nature.”

The gunman in Christchurch, responsible for the murder of 51 people, referred to himself as an ‘ecofascist’ and published a 75-page manifesto which called for ‘Ethnic autonomy for all peoples with a focus on the preservation of nature, and the natural order’ and was brimming with white-nationalist language and outlined a blueprint for copy-cat shooters.

The El Pas shooter, who gunned down 22 people blamed American consumer culture for ecological damage and stated that “If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can be more sustainable.”

Although these are examples, they demonstrate how harmful this rhetoric truly is and how it can contribute to violence.

Decolonising the Environmental Movement – The Future is Intersectional

As we run out of time to avoid climate catastrophe and get increasingly desperate to lower emissions and restore biodiversity, we risk more ecofascist ideologies seeping into the movement. If we’re not paying attention to how white supremacy shows up, there is a very real threat of a ‘by any means necessary’ approach led by wealthy states at the expense of the dignity and rights of poorer nations. If that happens, we might ‘save the planet’ for just one type of person. Without taking an intersectional approach to climate action, we are doomed to uphold the status quo and all of its injustices, rather than using this challenge as an opportunity to rebuild our systems to create a better, more equitable world for everyone.

Mary Annalise Heglar, climate activist, shares “So you can see this crisis coming and say ‘shut the borders, we’re going to have limited resources and those resources are going to be for me and mine and no-one else’ and that is already happening. People will say, my biggest fear about climate change is how people are going to treat each other. My biggest fear is how white people might treat me.”

We can do things differently by focusing on climate justice, honouring Indigenous knowledge and uplifting the voices of marginalised people. “Indigenous peoples have long stewarded and protected the world’s forests. They are achieving at least equal conservation results with a fraction of the budget of protected areas, making an investment in indigenous peoples themselves the most efficient means of protecting forests.” – Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, United Nations Special Rapporteur.

Intersectional Environmentalism “identifies the ways in which injustices affecting marginalized communities and Mother Earth are interconnected. Intersectional Environmentalism not only acknowledges these links but brings them to the forefront.”

Educated women

Project Drawdown lists the education of women and girls as one of the most effective climate solutions. Over 750 million people in the world are illiterate and two-thirds of those are women and girls. Factors like extreme poverty mean that girls around the world face many barriers to accessing an education. However, we know that investing in girls not only makes for smaller and healthier families, it also lifts economies. Rather than focussing on and funding oppressive reproduction control, if we can invest in educating women and girls we are not only ensuring they delay marriage and children but also that their freedom of choice, their human rights and their dignity are protected too. Smaller populations will be a bi-product of empowering women and ensuring they have agency of their own lives and family planning.

Eradicate Poverty, not freedom

Poverty is the primary barrier to education and is what keeps women from achieving equity. There is already enough money to eradicate poverty but just nine of the world’s richest men have more combined wealth than the poorest 4 billion people. The problem is not that we don’t have the capital or the solutions to solve the world’s biggest challenges like extreme poverty or climate change, it’s that the people who have power over that capital that could be invested in solutions do not have the will. Our system has facilitated the hoarding of the majority of the world’s wealth by a very small group of people and has led to the richest 22 men in the world have more wealth than all the women in Africa. In order to solve the poverty problem, we need to redistribute global wealth through tighter legislation on multi-national corporations and effective taxation systems on the wealthy.

Tackle Food waste

An estimated 821 million people go hungry every day but we waste one-third of the food produced. What makes this even worse is that this food waste is expediting climate change and contributes to around 6% of greenhouse gasses. Through the radical transformation of our food system – from the way we farm to the way we distribute food, we have the opportunity to ensure everyone has a healthy balanced diet that is in harmony with the planet. Healthy soil means healthy food and healthy food leads to healthy people. By switching to a diet focussed mostly on plants and what is seasonally and locally grown, we can sustainably feed the global population.

Final thoughts

Climate justice is social justice. Like most systems, the environmental sector has work to do. By shedding our colonial roots, we have a unique opportunity to simultaneously address societal inequalities and injustices alongside stabilising the climate and restoring biodiversity. Many of the solutions already exist and by ensuring varied perspectives are heard at every level of decision-making we can truly create a world that is better for everyone.