A team of researchers claimed that renting clothes is worse for the planet than throwing them away. Fashion Revolution‘s annual Fashion Transparency Index concluded that progress on transparency “is still too slow” in the global fashion industry. Ultra-fast fashion is making a comeback via TikTok. Is the fashion industry getting better, or is it all greenwashing?

Is renting and recycling clothing sustainable, or are brands just greenwashing us?

Recently, Fast Company published an article that made its rounds within the sustainable fashion space. The headline reads “Renting clothing is worse for the planet than just throwing it away, study shows”. And the byline, perhaps more damning: “Brands are trying to convince us that recycling and renting clothes is sustainable. A new study suggests otherwise.” Controversial and clickbait headlines aside: let’s discuss. Are brands really just greenwashing? Did the team of researchers behind the study really say that we shouldn’t bother with renting and recycling clothes?

The answer? Not quite. The study, as it turns out, is more nuanced than the headline suggests. In short, the study, and the team of researchers who carried it out, is a reminder that (sustainable) fashion has a ways to go. That rental models and recycling solutions aren’t perfect. And that brands touting that they’re “sustainable” are being rather misleading.

Renting clothing is worse for the planet than just throwing it away, study shows https://t.co/aGICm20UoV

— Fast Company (@FastCompany) July 7, 2021

Let’s get specific: what did the study find?

The study calculated greenhouse emissions from “five different ways of owning and disposing of clothing, including resale, recycling, and renting”. The researchers wanted to find out the data behind these so-called sustainable fashion alternatives, to see if the numbers actually backed the claims up. They found that renting clothes had the highest environmental impact, and according to them, even higher than just throwing clothes away. They also found that recycling too had a high impact.

Why are the emissions so high? For one, rental models depend heavily on transportation and dry cleaning services. Renting clothes involves the garments making many trips back and forth, along with wash cycles in between. All these add up in terms of environmental impact. And what about recycling? It turns out that industrial recycling processes generate a ton of emissions: recycling isn’t as simple as you’d think. (Not to mention, the industry still deals with its waste crisis by exporting unwanted clothes—either the stuff that doesn’t get sold at thrift stores, or the stuff that brands take in for “recycling”—all the way to the Global South.)

But does that mean we shouldn’t invest in rental and recycling solutions? The team of researchers isn’t actually saying that. In fact, Anna Härri, a co-author of the paper, said that they’re not trying to discourage brands from looking into these alternatives, but rather that “it’s important to realise that recycling and rental generate significantly more emissions than resale or simply wearing your clothes longer. This should inform how the fashion industry evaluates how to be more sustainable going forward.”

In other words? Just consuming less, and wearing your clothes longer is still the best option.

What’s the bigger picture?

The bigger picture that the study is getting at is this, as Härri shared: “For the fashion industry to become more sustainable, both consumers and brands need to move away from the entire concept of fast fashion.”

Brands aren’t doing enough to acknowledge that the best option is still to consume less. And the team of researchers is trying to remind consumers that the truth is that just because brands pursue or include rental or recycling alternatives, doesn’t mean that they’re sustainable. Or, more accurately, that these alternatives, as they are presently, are really only sustainable to an extent. And to suggest that they’re saving the planet would be at best, inaccurate, and at worst, misleading.

The researchers point out that “circular economy” has become somewhat of a meaningless buzzword in the fashion industry. Not because the concept itself is problematic, but rather because of the way brands in the fashion industry have misused it. Rental and recycling alternatives, for example, do get at the concept of the circular economy. They can and do keep clothes circulating for longer within the economy.

However, a truly circular system is the total opposite of our current linear system. It means that we don’t make more, and we don’t throw away. So for brands to co-opt one small aspect of the circular system, like renting and recycling, and then marketing their entire company as sustainable… is greenwashing. And frankly, doing a disservice to the circular economy concept.

Let’s talk about renting

Recycling is a whole other beast to tackle, so for now, let’s just talk about renting, which can help us distil the greenwashing point further.

Renting is greenwashing primarily on two levels. As explained earlier, the alternative involves a lot of transportation and washing, which as we know, aren’t very good on the emissions front. So the numbers don’t quite back up the claims. But on another, more big picture level, renting is greenwashing because it doesn’t solve the root problem. That is, the root problem that overconsumption: the fashion industry’s biggest sin. Consumers are buying too much, the industry is producing too much, and much too fast—and consequently, at the cost of our environment, and garment workers.

As Härri noted, rentals are premised on the idea of cycling through trends quickly. Have you ever seen ads for clothing rental companies? The promises of new wardrobes every other week? Changing out your clothes once you get bored of them? Having access to what essentially is an infinitely-sized wardrobe? That’s not sustainable. Desiring to constantly be keeping up with trends, whether it’s fast fashion or renting, isn’t sustainable.

Aja Barber, fashion journalist, stylist and author, has been saying this for two years now. In a recent Patreon-exclusive post, Barber shared: “Ultimately I don’t think rental services are challenging the idea of consumption at all. It’s still peddling the same myth that you need new clothes as often as possible. And that is exactly part of the problem.”

To be fair…

But to be fair, it’s worth pointing out that there may be smaller-scale rental models that are more sustainable. Certainly, local, peer-to-peer services are much more sustainable than big rental models, such as Rent the Runway. These bigger companies operate at a much larger scale, and because of that are going to run up against issues of operating sustainably more so than the smaller ones.

And, as producer, presenter, and sustainability activist Venetia La Manna shared in a recent Instagram post: “Like everything that started with genuinely green intentions, the rental model has been hijacked by billion-dollar brands like Ralph Lauren and greenwashing chiefs like H&M, with zero accountability for the vast scale, fast-turnover fashion that is harming garment workers, promoting needless consumption and contributing to climate breakdown.” This is to say that there are different brands, companies and corporations in the rental game. And so there are some with more greenwashing intentions than others. (We’ll leave you to guess which is which.)

And it’s not like rental models aren’t improving. In the wake of the publication of the unfortunately misleadingly-headlined Fast Company article, companies like Oxwash have been quick to respond. They, for example, have claimed that better laundering methods are in the works. And that rental is the future.

But is it improving fast enough?

Granted, we shouldn’t hold these smaller companies more accountable for improving the fashion industry than corporations like H&M. Massive corporations should be doing most of the heavy lifting, not startups and brands that are trying their best.

But we can hold all of these things at once. And say that even though we don’t expect rental companies to do everything, we should expect that they remain honest and not mislead their customers that an infinitely-sized wardrobe is sustainable. Especially when in-between rentals, wash cycles and dry cleaning practices are still emitting way more than necessary. And when rental companies are still profiting off privileged consumers’ desires to consume endlessly and keep up with trends. (The word “privileged”, of course, is there for a reason. We haven’t even started talking about how rental services are inaccessible to lower-income consumers!)

But to move away from rental companies—after all, this isn’t us coming for rental companies and trying to cancel them. In the spirit of reminding ourselves that massive corporations and bigger companies need to be doing much more work, let’s look at the Fashion Revolution Fashion Transparency Index, which examines 250 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers.

Is the fashion industry moving fast enough?

Are the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers pulling their weight? Or are they, too, greenwashing?

In its Key Findings, Fashion Revolution states that progress on transparency “is still too slow”, “with brands achieving an overall average score of just 23%”. That’s about the same as last year, and although part of that is because of Fashion Revolution’s expanded methodology, the organisation itself commented that still, not much has moved and the result is still disappointing.

The 2021 #FashionTransparencyIndex is here: https://t.co/TYgMcjIsm2

Discover how much the 250 largest global fashion brands and retailers are telling us about their supply chain and social and environmental impacts.#WhoMadeMyClothes? #WhoMadeMyFabric? #WhatsInMyClothes? pic.twitter.com/Jzos4KKzdN

— Fashion Revolution (@Fash_Rev) July 7, 2021

The Fashion Transparency Index 2021

The report highlights that there are several crucial areas in which brands are failing on being transparent. What concerns us most recently is the COVID-19 response: just 3% of brands and retailers are publicly disclosing the number of workers they’ve laid off because of the pandemic, and less than 18% of major brands are disclosing percentages of their order cancellations. All of this means that we don’t have a clear picture of the extent to which major brands and retailers are failing their garment workers during the pandemic. From what little we already know—it’s bad.

Another major area of concern is living wages. Activists have been demanding for living wages for years now. A living wage is in fact recognised by the UN as a human right because enacting it would mean workers have better access to healthcare, transport, food education, the ability to live with loved ones, to sleep, and more. And yet, according to Fashion Revolution, 99% of major fashion brands do not disclose the number of workers in their supply chain that they pay a living wage to. 96% have no roadmap towards this either.

There’s more, but for our purposes, we’ll just talk about one more: on addressing the climate crisis. Fashion Revolution reports that only 14% of major brands disclose the overall quantity of products they make annually. This means that we can’t even understand the scale of overproduction, even though we know there’s a lot of waste. Not to mention, most carbon emissions occur at processing and raw material levels, but only 26% of brands disclose information about processing and only 17% about raw materials.

Fossil fashion?

Let’s segue briefly to talk climate change. In late June, Changing Markets Foundation dropped a report titled “Synthetics Anonymous: Fashion brands’ addiction to fossil fuels”. It analysed almost 50 major fashion brands, from high-street, to sportswear, to luxury, to department-store companies and more, on the amount of fossil fuel-based materials in their collections and commitments to move away from them. Further, they also scrutinised 12 brands and over 4,000 products to find out the truth about their sustainability claims.

The results? “While some brands are making commitments to move away from using virgin polyester, they make no such commitment regarding synthetics in general.” And worse, even when they say they don’t want to use new polyester, most brands replace that with downcycled single-use plastic bottles. Changing Markets Foundation highlights that this is a “false solution”. It doesn’t adequately address either the issue of massive overproduction by these major brands or the harmful impacts of the production of these bottles to begin with. At worse, if fast fashion becomes dependent on these single-use plastic bottles, it might even end up prolonging the transition away from single-use plastics.

If they really cared about climate, then they wouldn’t be prolonging the addiction to fossil fuels. Changing Markets Foundation reports that synthetic fibres represent over two-thirds of all materials used in textiles. A figure that’s expected to balloon to nearly three quarters by 2030.

Greenwashing is the season’s hottest trend

And most concerning of all? These major brands are taking the fact that they do one somewhat sustainable thing, and claiming the sustainability label. If you thought rental companies misleading consumers was bad enough, this is worse.

According to Changing Markets Foundation, greenwashing “is rife”. “The majority of brands made sustainability claims, and 39% of the products studied had a green claim attached to them. A closer look at brands’ policies, targets and commitments revealed that greenwashing is clearly this season’s hottest trend.” Some brands claim that synthetic products are recyclable even though the recycling technology doesn’t exist. And when they label their products as “sustainable”, or “responsible”, or, our personal favourite, “conscious”, there’s no supporting evidence for these claims.

So basically, they’re saying claiming to be doing something, when really they’re not. Or, they’re doing something, and it’s not really actually making a difference. All while not even addressing the fact that even if these were all sustainable (if, for example, all these sustainable products were made out of truly recyclable materials), the rate at which they produce them is still not sustainable.

In the end, major brands and retailers too, still aren’t looking at the bigger picture.

The biggest losers

We need to remember that if the fashion industry isn’t moving fast enough, the biggest losers are out of sight, and too often out of mind. What is the cost of major brands and retailers greenwashing? Of rental companies peddling the myth of needing to buy more and buy new? Of report after report revealing that progress in the industry is far too low? The cost is borne by the planet, yes. But aside from the environmental cost? There’s a human cost too.

If the industry isn’t critically examining itself, it ignores the root problem of overconsumption. Overconsumption, which is fuelled by rapid production, which is in turn fuelled by ever-reducing costs… And a race to the bottom which renders the people at the ends of the supply chain disposable. The evidence? The ongoing exploitation of garment workers, documented by organisations like Clean Clothes Campaign, eight years after the Rana Plaza disaster—which should have been the industry’s wake-up call.

This is why Barber shared in an Instagram post just a week ago, plainly, that “the fashion industry is not “getting better””. “So it seems,” she wrote, “we still have an issue with folks obscuring how much stuff they’re slashing and burning which is A HUGE part of the problem and we still have CLEAR issues with treatment of individuals within the supply chain. So no. It’s not getting better. Nobody ask me that.”

So what? What do we do now?

If all of this seems dismal, that’s because it is. The reality is that progress in the most crucial parts—that is, the most vulnerable and marginalised communities who support the industry—is still too slow. Does that mean we dismiss the progress that has been made? No. To return to what Härri shared, this doesn’t mean that we should discourage companies who are pursuing alternatives from doing so. And Barber, I imagine, wouldn’t either.

What, instead, we could do, is be honest about where we’re at. Which is to not kid ourselves, to not greenwash, and to not, in the spirit of toxic positivity, claim that the fashion industry is getting better. We need to be more careful when we claim that alternatives are sustainable. We need to admit when it’s not sustainable, admit when more needs to be done, and admit when some has been done to make alternatives more sustainable, but not entirely.

And what does this look like?

We already see honesty in action

It’s worth pointing out that demanding more honesty from brands works. In another Patreon-exclusive post, Barber reminded us of the fact that even H&M can bend at the knee if enough consumers raise their voices. Last year, when Fashion Revolution released its 2020 Transparency Index, H&M came out on top. Not quite because H&M is the most transparent, but because brands had to have a minimum annual turnover of $400m to be considered for this index (aka: massive corporations—read: big polluters—only). Basically, they “essentially won “best of the worst” which is entirely different to best in the world”.

Anyway, H&M immediately put out posts on Twitter and Instagram claiming that they were the “most transparent brand in the world”. And people did not have it. Tons of people called H&M out online. H&M promptly deleted the post, and posted a non-apology five days later. It was embarrassing, to say the least, but the point is that consumers rallying against clear dishonesty and greenwashing works.

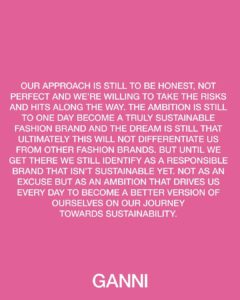

A few weeks ago, popular brand Ganni, often noted for being “in the sweet spot between fast fashion and luxury” came out with this post. In white, all-caps text, on its signature pink background, it shared: “We’re not sustainable. We’ve been saying this since 2013 when we took the first few steps towards a more responsible version of ourselves.” The post went on to share about why they’ve been keeping quiet, and what they’ve come up with. Whether or not Ganni is really doing better isn’t of concern here. That’s for the experts to decide. What we want to emphasise is this: an honest approach is the best kind.

What would happen if all brands, even the biggest polluters like H&M, started being actually honest about their (lack of) progress?

IMAGE: via GANNI | IMAGE DESCRIPTION: White text on a pink background. The text is in all capital letters. “Our approach is still to be honest, not perfect. And we’re willing to take the risks and hits along the way. The ambition is still to one day become a truly sustainable fashion brand. And the dream is still that ultimately this will not differentiate us from other fashion brands. But until we get there we still identify as a responsible brand that isn’t sustainable yet. Not as an excuse but as an ambition that drives us every day to become a better version of ourselves on our journey towards sustainability.”

We need to overhaul the industry

If we’re being honest about the industry, here’s the truth: we can’t keep going like we’ve been going. We can’t maintain the same levels of production. We need to consume less, think more locally and more ethically. That way we can actually begin to work towards a real circular economy. And we need to think smaller. Part of the problem with the fashion industry today is because it’s so massive. The bigger you get, the more difficult it is to be sustainable, because at some point, brands end up merely chasing profits.

Barber commented under a recent Fashion Revolution Instagram post that the Index should “do more than give big brands a chance to show off how they’re failing while pretending like it’s progress.” She suggested that the Index made direct comparisons of these major brands and retailers to smaller brands, which she knows are already showing that it’s possible to have a fashion industry that’s more sustainable, and more ethical. That actually cares about its workers, and about its garments—and how they’re loved.

Perhaps we’re looking at it all wrong. Indeed, as Barber alluded to, looking at these big brands might make us feel hopeless. But we just need to turn towards smaller brands that are showing that it’s possible to do better. “If there was a direct comparison”, she said, “people might start to grasp the importance of small business and why we should champion the David’s. It would also light a fire under the Goliath’s [that’s H&M and co.] to clean up their mess more.”

What about consumers?

What can we do? To further encourage the industry in the right direction, we just need to be consistently using our voice where we can. Unfortunately, unless you work in the industry, it’s not that easy to get materially involved with the changes that need to happen. But lucky for us, there are many organisations and activists you can amplify and support. Fashion Revolution and Clean Clothes Campaign are two examples, and Aja Barber’s voice is a particularly influential one. These voices function as watchdogs for the industry—watchdogs that the industry is listening to.

And if in the end, the root problem is overconsumption, then a culture shift is needed. And that culture shift can happen with the help of us individuals, collectively, buying less. Most of us really just need to rethink the necessity of our wardrobes changing every season. Can we, instead of buying new clothes, look to keep our existing garments in our wardrobes instead? Look to mend, repair, rework, upcycle them instead? As Fashion Revolution often repeats, #LovedClothesLast. Not only does this encourage us to have better relationships with the stuff we own, but it helps us honour those who make it too.

A system change is needed, but that won’t happen without cultural shifts, without us using our voices and platforms for good. To see a better fashion industry, we must demand for it.