During COP26, we saw public discourse finally acknowledge gaps in representation within the environmental movement and in climate justice solutions. Outside the talks, we saw a positive shift with the amplification of Indigenous voices, frontline communities and youth activists. But, there was one community still woefully underrepresented – people with disabilities. We take a look a the intersection between disability rights and climate change.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified over 1 billion disabled people using the definition that “a disabled person is anyone who has a problem in body function or structure, an activity limitation, has a difficulty in executing a task or action; with a participation restriction”. Disabilities may be cognitive, developmental, intellectual, mental, physical, sensory, or a combination of multiple factors. They can be present from birth or acquired during a person’s lifetime. In fact, 80% of disabilities are actually acquired between the ages of 18 and 64, when people are more likely to be in the workforce. Simply put, anyone could become disabled at any point in their lives. And every year, the number of people affected by disability is rising. The WHO explains that this is due to an ageing population and an increase in chronic conditions. Disability rights must be an integral part of climate plans.

Disability Rights

It is a shameful truth that people with disabilities faced centuries of stigmatization and marginalisation. While the world remembers the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s in great detail, another battle raged in tandem. People with disabilities had had enough and joined forces to change both public attitudes and government policies. Disability Rights advocates seized the opportunity to fight alongside other groups to demand equal treatment, equal access and equal opportunity for people with disabilities. Following decades of campaigning, protesting and lobbying, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed in 1990. This set a new precedent and nations around the world followed suit.

While much progress has been made, people with disabilities still face daily challenges as they navigate their lives in a world that was not built to accommodate their needs. Capitalism values people according to their ‘productivity’ and ability to work as ‘contributing to society’. Disabled people are often unable to work traditional jobs or standard hours and are still largely excluded from the workplace. As a result, they are more likely to live in poverty.

The last straw

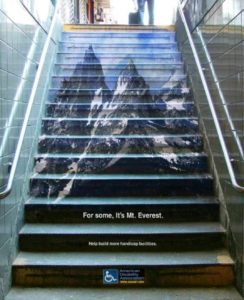

In London, 75% of underground stations are still inaccessible. And elevators in the 25% are frequently ‘out of order’. This means that people with disabilities that affect their mobility have to spend considerable time and energy planning their trips. In a lot of cases, it is easier to use taxi services to save some of that time and energy but that also comes at a cost. To their finances, and to the environment. When we advocate for active travel and public transport as solutions to the climate crisis, we frequently neglect to consider the impact this would have on people with disabilities.

Another infamous example of an environmental action that failed completely to consider the needs of disabled people, is the campaign against plastic straws. Despite only making up around 1% of plastic waste in the sea, a viral video of a turtle with a plastic straw lodged in its nose and a growing ‘zero-waste’ movement contributed to the straw becoming the fall guy for the plastic problem. Campaigners lobbied for an outright ban and won in many countries. While environmentalists celebrated a win, the disabled community quickly pointed out that many people rely on plastic straws every day. Going out to eat can already be fraught with complications and taking away plastic straws has now added another one for millions of people.

People with disabilities are not a monolith. Like every other marginalised community, disabled people have a unique experience of life. They have different needs, different privileges, different life experiences. And many care very deeply about the climate crisis. They want climate solutions, but they were inclusive climate solutions.

When disaster strikes

Climate is a threat multiplier – disabled people are 5 times more likely to die in a natural disaster. The global average temperature has already risen by 1.2°C, bringing on a huge increase in extreme weather events. And even if a disabled person survives a disaster, the lasting impact on them is still greater than that of someone who does not have any disabilities. They can lose homes built to accommodate their needs, specialist (and often expensive) equipment they rely on and medicine.

Almost half a million people with disabilities lived in the counties and parishes affected by Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The evacuation and emergency plans did not account for this.

Jordan Melograna reporting for the Huffington Post shares, “There was no plan to transport wheelchairs or provide electricity for ventilators. There was no pre-planning for evacuating hospitals and nursing homes. No accommodations were made for people who are Deaf or blind inside emergency shelters. The list goes on, touching on every right that people with disabilities fight to have in everyday life, which went simply went unaccounted for in the emergency. This wasn’t a plan that overlooked inconveniences that everyone experiences in these scenarios, this was a plan that overlooked important, life-preserving accommodations that many people with disabilities need in order to live.”

The death of Ethel Freeman, 91, became a symbol of government failure. She perished, abandoned, outside an overwhelmed emergency centre. The family later sued. Their lawyer issued a devastating reminder, “Let’s not forget, she survived the storm. The storm didn’t get her. She didn’t survive the rescue.”

16 years later, regrettably, things have yet to really change. In the summer of 2021, the world watched with trepidation as a wave of floods engulfed Europe. In Germany, more than 100 people died including 12 who were living in an assisted living facility. The evacuation plans had not accounted for people living with additional needs.

The Right to be Rescued

“The Right to be Rescued” was released to mark the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. The filmmaker’s mission was to make emergency planners aware of the specific needs of people with disabilities and persuade them to modify disaster plans to ensure sure those needs are met.

Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, but disasters like earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, or chemical spills can strike anywhere at any time. The purpose of emergency planning is to think ahead. Emergency planners everywhere have a responsibility to devise plans that include everybody. Because everyone has the right to be rescued.

80% of disabled people live in the Global South. The Global South has been feeling the effects of climate change for a considerable time already, and this has a devastating impact on people with disabilities. There is a platitude of reasons for this, many of which stem from economic disadvantage and struggling healthcare systems. If disabled people in some of the wealthiest countries in the world are left behind in emergencies, what chance do people have in poorer nations with less funding?

Climate Policy

COP26 was heavily criticised as the ‘least inclusive’ COP ever. This was partly due to continued COVID restrictions which made it difficult for participants from the Global South to attend. On top of that, was the problem with accessibility for the event itself. COP26 was two years in the making but the accessibility assessment was carried out last minute. The group that conducted the assessment raised a host of issues but there were not addressed and the organisers initiated the conference knowing that it was not an accessible space for people with disabilities.

Pauline Castres is a policy expert in climate justice, disability rights and global health. The hybrid format meant that she could attend the talks remotely but was disappointed by the lack of representation for disabled people in decision making positions. Pauline remarked that “we were made to feel grateful that there were one or two events that talked about disability but in truth, disability should be a part of every conversation. It felt like disability never existed. The climate space often sees disability as a consequence of climate change. It is an indicator that is used to measure the impact of climate change on global health. But, people who are already disabled can be a part of creating solutions.”

Castres explains that even when disability charities are invited to attend or speak, this does not necessarily mean that disabled people are truly represented because most of those non-profits are led by non-disabled people. However, there are other organisations called Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) that must be made up of at least 70% of people with lived experience of disabilities. The UK has been called out regularly for not engaging DPOs. This was evident at COP26. Castres would like to see much more consultation with DPOs in future COPs and other important forums where climate solutions are discussed and planned.

Building coalition

Of course, there is more to climate spaces than COP so what can we do to make the climate movement more inclusive?

Firstly, Castres says, organisations need to be aware that there is a lack of representation. And they need to reach out. She explains that “Disabled people are so busy just surviving. We have to self advocate all the time for access to employment, education, benefits or healthcare. It means unless there is a flood at my door I’m not thinking about the climate so much. We need to get people out of poverty because you can’t do anything about the climate if you are completely ostracised from participating in regular life.” With this in mind, it’s important that organisations reach out to disabled people and ensure they know they are welcome to join. Local groups in the environmental space need to prioritise connecting with groups and organisations that work with disabled people and begin to build relationships.

Inclusive activism

The next step, Castres says, is to ensure that members of the group or organisation receive adequate training. There have been a lot of surveys carried out about how people feel when they are around disabled people and the most common answer is ‘awkward’. Disability advocates have worked hard to challenge perceptions and shift the culture but there is still a lot of work for all of us to do in this regard. Training helps group members better understand the diversity of disabilities, the experiences of people who live them and challenges stereotypes. If organisations invest in training, it will create a more comfortable atmosphere for everyone, conducive to successful collaborations.

And it goes both ways, we can also facilitate training for disability activists on climate too. There is so much we can learn from each other.

In addition to this, we need to examine the ways in which we participate in climate action. Protests and demonstrations are commonly used but are not always safe and accessible. As activists, we need to ask ourselves how we can make those spaces and actions more accessible. Another question we can ask is how to can people come together in alternative ways to show their resistance? We take to the streets in the form of protests to raise awareness and apply pressure. We need other tools and disabled people can get involved with those.

> Continuously challenge your own perception of disabilities and disabled people

> Read books written by people with lived experience of disabilities

> Watch 2020 documentary ‘Crip Camp‘

> Ensure disabled people and DPOs are part of your consultations and decision-making process

> Make your spaces and content accessible with things like captions for videos, wheelchair access to venues, remote access for people who can’t attend in person

> Look into your localities emergency plans and if they are not inclusive of disability needs, write to the planners and politicians responsible